This post is a part of the online special edition Peter Beilharz: The Life of the Mind, Friendship, and Cultural Traffic in Postmodern Times

by Christopher G Robbins and Eric Ferris with Sian Supski

Now no one can at the same time be both jealous and grateful, because those who are jealous are querulous and sad, while the grateful are joyous.

Seneca, On Benefits

Who is Peter Beilharz? One of the most sophisticated scholars of Marx and marxism in the last 40 years? The Theorist of the Antipodes? The Interpreter Exemplar of the Interpreters? Gifted pedagogue? Producer and conductor of (global) cultural traffic? Essayist? Reliably challenging thought partner and kind friend? Tireless historical sociologist of socialism and modernity? Unabashed modernist, as one of his trademark t-shirts wryly indicates? Highly esteemed mentor? Maybe, though others would suggest more bona fides still.

On the one hand, those who are convened in this collection and who have known Peter the longest and most intimately should, and do, answer the question: Who is Peter Beilharz? Our individual relationships with Peter stretch only years, while others have had the good fortune of experiencing decades with him. On the other hand, both of us were raised to form impressions of people not by how they initially appear to us, but by what they have done, how they conduct themselves, and what they seek to do with and for others in the world – by their projects and their ethical coherence, the degree of overlap between word and deed. These indicators provide a solid working set of terms to develop an understanding of the ‘who’ that exists behind the appearance. So, how might we suggest others think about Peter? As an intellectual? Yes, for certain, but what critical qualities might get nudged out of view by thinking of him only in this way? As an educator/mentor? Definitely, but again, characterizing him only in this way pushes other important elements out of the frame. What about Peter as a friend/thought partner? Affirmative, but such a singular characterization elides what people know about his intellectual and pedagogical work. As it is with gems, too, one facet of Peter has to be appraised alongside the others. His works in the wider world are tightly melded with his work in the classroom (still) and his commitments to friendship.

To describe this project as a festschrift seems fitting. It is, indeed, a collection of writings gathered together to honour, or pay tribute to, Peter as a scholar. The metrics describing Peter’s scholarship – his contributions to sociology, historical sociology, and social and cultural theory – reflect both its volume and quality and make him fitting of such a tribute. In an academic world in which it is quantity that defines one’s worth, Peter has produced rigorous and serious scholarship, and in bulk, such that his body of work might easily surpass that of the collective scholarship of faculty in many moderately-sized university departments. He has published deeply historical works ranging from Trotsky, Trotskyism and the Transition to Socialism (1987) and Labour’s Utopias: Bolshevism, Fabianism, Social Democracy (1992) to theoretical tracts like Postmodern Socialism: Romanticism, City and State (1994a) and then-contemporary analyses like Transforming Labor (1994b). He has also provided wider interrogations as in Socialism and Modernity (2009), while theorizing the antipodes in Imagining the Antipodes (1997) and Thinking the Antipodes (2015). Recent work also includes contributions as different as Circling Marx – Essays 1980-2017 (2020a) and Toward the Blues (2023), with many more between 1987-2023, and even more to come. There are also the textbooks that he has authored, co-authored, edited, and co-edited, as well as his studies of intellectuals, such as Zygmunt Bauman and Bernard Smith. In addition to these significant works, there are the differently significant works, to the tune of a few hundred book chapters, peer reviewed articles, and book reviews. If this complex body of work does not speak for itself, Peter has been the awardee of various grants, tied to projects like ‘Jean Martin and the Social Sciences in Australia’ and ‘The Pursuit of Social Harmony in the Antipodes’. Then there are the distinguished international appointments awarded to him, such as Professor of Australian Studies at Harvard University and Fellow in Cultural Sociology at Yale University, among others, for which his unassailable mastery was rightly recognized. In other words, even considering the corporate university’s abusive model, Peter stands above many for not only the quantity of his work, but also, and more importantly, its characteristic depth and complexity, along with his value for collaboration that brushes against the grain of the corporate knowledge factory’s intensively individualistic and competitive culture.

Worthy of a tribute – a festschrift? Unquestionably so, but a tribute to only his scholarship would provide a grossly incomplete picture of Peter, especially against the backdrop of the corporate university’s metric fetish that would, perhaps, pay tribute to only Beilharz, rather than Peter, too. In other words, terms matter. Such a tribute cannot merely focus on his vast published work, but must begin to appraise and celebrate the entire person and body of works attached to Peter the intellectual, the friend/thought partner, the educator and mentor. It must register and celebrate Peter’s many gifts that are at once inextricable from his work and invisible to the metric fetishists: the multitudinous relationships – intimate, mentorly, social, political, cross-/inter-/trans-continental and intercultural – that endear Peter, PB, Peter B, Pete, and Beilharz to so many. And who better to bring these various qualities into relief alongside his scholarship than those who can speak to them best: his intellectual friends, current colleagues, and past students?

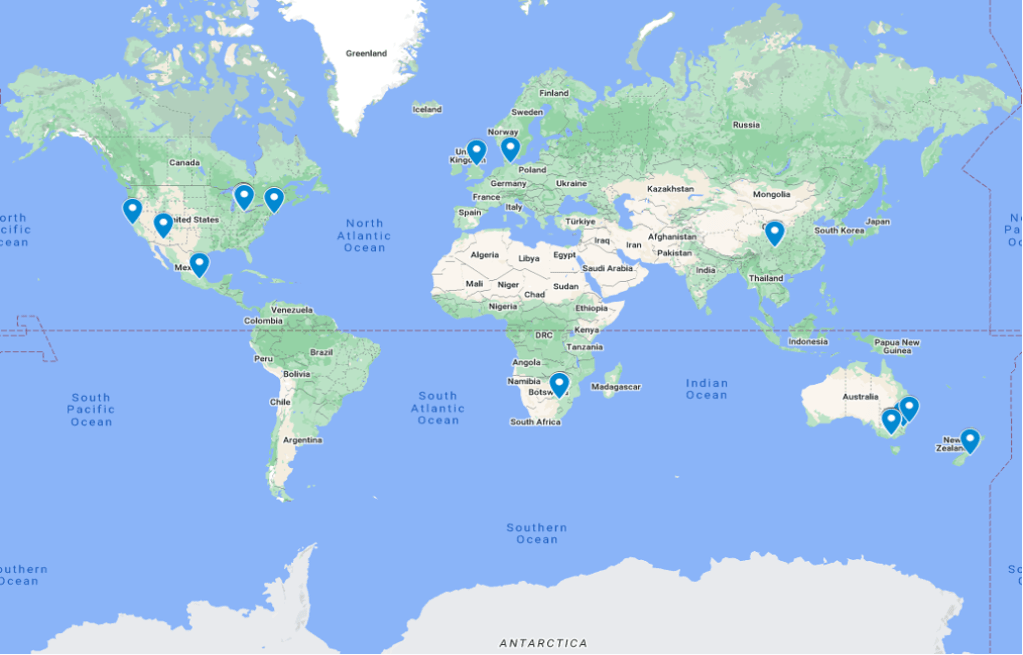

So, let’s consider the b-side of Peter’s record – the side that shows why so many would rush in to pay tribute to him, as a scholar and, more importantly, as a friend. Looking through his career highlights, he regards working with Alastair Davidson at Monash; the team at PIT Sociology, including Rob Watts, Kerreen Reiger, Mark Considine and John Murphy; Stuart Macintyre at Melbourne University History; and being appointed to the position vacated by Agnes Heller at La Trobe as crucial in his career development. He is a visiting professor at the Bauman Institute at Leeds University and is widely recognized not only as one of the leading interpreters of, even a specialist on, Zygmunt Bauman, but also Bernard Smith. Even considering the significance of these academic distinctions, our experience with Peter would suggest that such achievements would ring hollow if it weren’t also for the friendship, care, and affection he felt for both. There is also his career-spanning work with the internationally renowned journal Thesis Eleven, as one of its founding editors, and his direction of the Thesis Eleven Centre, both of which, seminally, are major conduits for cultural traffic between the Bauman Institute in Leeds, the Yale Center for Cultural Sociology, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines, the University of Delhi’s English Department, the Socio-Aesthetic Unit at the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Witwatersrand, City Institute, in Johannesburg. Rather than the accomplishment of having established such an enviable set of relationships be the focal point, it is the global production and exchange of dialogue, of friendships, of teaching and learning that make the connection of these dots on the world map important. A network, possibly, but one that replaces quantity and ‘dis/connection’ with cross- and inter-cultural communication, engagement, and deep relationships, all constituting a diverse, inclusive, global community of ideas, itself running against the grain of a world that militates against such conviviality, curiosity, and mutuality. If we could twist a phrase from Peter’s Thinking the Antipodes (Beilharz 2015)[1], it is a vast world connected by small cognitive and moral distances, with Peter, and, fortunately, so many others, many in his circle, who work to ‘shrink’ the distances in-between and do so with care, trust, affection and, above all, friendship. We provide one view of these relationships in the map below – the geographic locations of contributors to this project. This, of course, is why liber amicorum seems to be a more fitting characterization of this volume: It is a ‘book of friends’ – a collection for our friend, from (some of) his friends, centralizing friendship, critical and collaborative, intimate and intellectual.

Friendship ↔ Gratitude

A simple yet ineffable virtue provided the impetus for this liber amicorum: gratitude for Peter Beilharz, his vast body of work, and his friendship. However, a puzzling set of tautologies emerges when one probes the concept of gratitude. A scan of the literature quickly shows that gratitude regularly appears with joy, with gratitude getting construed as the expression of joy for that which brings one joy, and joy being a common medium by which people express gratitude, a tautology within a tautology. So, what is joy? A slightly enlarged experience of happiness? Perhaps joy could be characterized this way in a ‘society of individuals’ (Bauman 2008), a society in which our social energies get trained singularly upon the maximization of the unattached self, the actually existing dependencies masked – and denigrated – by the triumphalist individual, foundational relationships and bonds be damned. Rather, we find joy, unlike happiness, somewhere else. Joy springs from sources beyond the self, in the relationships in which one participates. Others produce and bring joy to us, hence we demonstrate gratitude. Since joy tends to appear with gratitude, the preposition matters: We most often express gratitude for – and feel joy because of – someone, some set of others – for the good they engender and cultivate, and the relationships that bind us to them. We don’t, and it should not have to be said, experience gratitude against something. If we felt or had gratitude against someone or something, joy would transmute into jealousy or relief, not delight or exultation. Given the social sources of joy, we may – and likely should – experience gratitude with others, for someone and for the relational grist that feeds our bonds to each other, and the other. For this reason, friendship, even the more utilitarian kind of civic friendship pondered by Aristotle and sorely lacking in the most powerful (and dangerous) parts of the world today, would seem to provide the fertile soil in which gratitude grows and on which we express joy. As the empiricists would have it, too, the demonstration of gratitude and its concomitant joy underpins a potential dynamic wherein the source and recipients of joy tighten and deepen their bonds of reciprocity, of mutual support (solidarity?) and its requisite elements of trust and respect (Wood et al. 2007).

Seneca’s (1912) classic On Benefits comes to mind, and for good reason. He dedicated ‘Book III’ of his letters to gratitude. Whether a benefit appears in the form of a serendipitous gift, aid when one experiences need, or as the outcome of mutual interactions (e.g. a sense of belonging or appreciation that emerges from the provision of care or friendship, or someone opens a window or door to new possibilities or choices), Seneca contemplated the critical importance of the recipient to acknowledge the act (or, as it may be, the many acts!). It is both good and a good – as in a common good, rather than a commodifiable good – to express and share gratitude. As he argued, one who fails to take time to demonstrate such appreciation is either forgetful or self-interested/-serving, focused on the pursuit of current or future opportunities. A short memory for good acts erodes the grounds for mutualism, respect, and trust just as much as a desire to capitalize on those good acts, even if the motivations differ in each case. Seneca consequently distinguished between ‘repayment’ and gratitude. Paying a debt, he claimed, ‘requires gratitude, time, opportunity, and the help of fortune; whereas, he who remembers a benefit is grateful for it, and that too without expenditure’ (Seneca 1912: 54). Seneca (1912) continued,

Since gratitude demands neither labour, wealth, nor good fortune, he who fails to render it has no excuse behind which to shelter himself; for he who places a benefit so far away that it is out of his sight, never could have meant to be grateful for it.

Seneca (54)

Small as gratitude might seem because it costs naught and the NYSE fails to index it, gratitude provides significant amounts of the small change of everyday life. Friendship, intimate or intellectual, cannot exist without gratitude. Without it, friendship becomes its other, transaction, opportunism, the society of, and for, one.

Friendship as a site and source of joy and reason for gratitude? Friendship as our primary relation of and medium for freedom? Friendship as a germinal site of solidarity? Friendship – intimate, intellectual, and political – with Beilharz, or, rather, Peter, suggests as much can be possible.

Let’s then return to the man of the hour, Peter, who lovingly penned a memoir on friendship, about his long relationship with Zygmunt Bauman in Intimacy in Postmodern Times: A Friendship with Zygmunt Bauman (Beilharz 2020b). This seems appropriate to do for a variety of reasons, not least because this book on friendship resonates, even with intellectuals. This is shown by a number of contributors in this liber amicorum who attest to, if not properly reflect upon, the power of this book. While one can read Intimacy as an outlet for Peter to process his grief, it can also be seen as a celebration of and commitment to friendship, because Peter makes a friend present, again, in his absence. Perhaps, Intimacy is also Peter’s note of gratitude to ZB. Even in opening himself up, in sharing himself at his most vulnerable, Peter’s light and lively humour – even disarming youthfulness – balances an abiding seriousness and intensity of focus on whatever stimulates his curiosities, whatever stones on which he grinds his axes or, as is the case in Intimacy, in the ways that he affirms hope in, through, and with others. Friendship for Peter is joyful. It’s gentle and kind, caring and respectful, and it fosters curiosity about the other and much else.

Friendship is, centrally on this register, serious for Peter. Friendship is not work, but friendship exists with and within work, as it would with someone who has consistently and ceaselessly operated at the most ethereal of levels in his commitment to the life of the mind for more than 50 years. (The calculation: His commitment would have had to begin in his teens; he co-founded Thesis Eleven at the ripe old age of 27 and, at 35, assumed the chair vacated by Agnes Heller, after all.) ‘Friendship’, in this regard, ‘is…inseparable from our work, from the problems we seek to make sense of, from the tasks we set ourselves’ (Beilharz 2020b: xi). Yet, it is more for Beilharz (2020b), in some ways being almost everything, the act of relating, the active being in relationship with, that ‘makes so much possible, even thinkable’ (xi). Friendship, and especially intellectual friendship, for Beilharz, is – it has to be – a radical practice, in everyday life as much as in the academy, because both spaces organize against the social self, the moral self, and privilege the aggressive, unfettered self-interested self, the academic as entrepreneurial self, the opportunist self. Go watch as much on TikTok, in blips, or on commercialized political talk shows in the U.S., brought to you by Viagra, BlackRock, and Lockheed Martin. The sidelining of the self for Beilharz, or at least the opening of the self to the other in the attempt to achieve understanding, seems to act as an everyday resistance, a movement away from the claws of power, more than a statement pitched directly in opposition to the world as it is, or as it is made to appear on our screens. Of anyone, Beilharz knows logic, and the logic of friendship cannot operate on the same terms as the world as it is currently ordered, on the logic of the cash nexus, even if friendship must negotiate and navigate the conditions associated with such terms. Here, we are reminded of something one of Peter’s teachers, Agnes Heller (1984), said early in Everyday Life in developing her concept of the individual: People are ‘born into a concrete world which has been more or less alienated. But it is not obligatory for every person to receive the world in its concretely given existence’ (19). Castoriadis (1997) and Simmel (1910) in their own ways also note that parts of the self remain unsocialized, unalienated, that refuse domestication and always threaten to rise against order, or simply act in the interests of another order. Peter received these messages, it seems, long before Heller and Castoriadis put them in print. Some individuals like Peter, and like the friendships he maintains, demonstrate and bring into existence other ways of being in the world and moving in relation to the world as it is concretely given, and great joy is found in fostering the relationships that support such a mode of being in and interacting with the world. For this fact, Peter, we express our gratitude by bringing your friends, some of whom have become our friends in the process, together in this ‘book of friends’.

Vast World, Small Cognitive/Moral Distance

So, a tribute – yes. A book for a friend by his friends – most definitely. But certainly there is more nestled fortuitously in the pages of this collection, another reflection of Peter and an abiding underlying message of his work? In at least a couple of contributions, Peter’s friends note the strongly-held differences in political philosophy between them and him. Of course, these contributions highlight noteworthy ‘friendships across difference’, no small matter in some of our quarters, as difference increasingly appears as an unbridgeable chasm – a gulf that appears to widen and deepen with each additional political ‘transgression’, real or perceived. These contributions not only provide an exemplary model of intellectual, political, and civic friendship, but also posit the hope that political difference and disagreement can – and should – exist, and it can exist on grounds of mutuality, trust, and respect, the goal being, as it needs to be, to achieve understanding, to find or produce overlap in horizons of meaning. These contributions demonstrate that difference is not an unbridgeable chasm to ignore or, as is increasingly the case, to fortify, but rather a precondition for and outcome of human togetherness. Difference, or diversity, remains a biological fact. Everything else about it we invent, to our promise – or peril. Without the diversity within, across, and between humans, our world would crumble, despite what those preaching nationalism, tribalism, or other closures of community claim in their attempts to construct a monoculture. It is to our collective benefit that people like Peter, and his peers, continue to challenge difference as a weapon and look to it as a resource, the outcome of cultural traffic that we need in order to go somewhere else, to construct a fairer and more just world. Grown out of fairness, mutuality, trust, and respect, we can disagree, but do so within a larger-than-me/my framework – a vocation, or work, that is dialogical, cooperative and collaborative, and builds a world where being for and with others that we materialize in our relationships as much as in our heads: a ‘we’, this suggests, that can disagree ‘politically’, and a ‘we’ that guards and catalyzes our commitment to a wider ‘us’, a promise to get beyond the isolated and aggrieved self and its narrowly delimited habitat.

Togetherness grows out of common work. It requires labor, and there is a politics to cooperation. Yet, there is pleasure to be had in it, too, as Sennett (2009 and 2012) has shown in two beautiful and important works of sociology. To give it a more fitting term, one with which any reader of Peter’s body of work would be familiar, togetherness, as we are referring to it, provides the performative and practical grounds for solidarity. In a set of institutional arrangements in which ‘unbridgeable’ difference seems to be the optic through which we ‘see’, or are led to believe we need to ‘see’, others, solidarity exists for target practice – it is made to appear as an abomination to the ‘natural’ order of things in modernity or postmodernity as-it-is (or as-it-has-been-made-to-be). Yet solidarity cannot but be what we must foster if our goal is a world where respect can be nurtured and trust presumed, where relationships form horizontally rather than vertically, and where the ‘what’ we do for others is done with our collective benefit in mind. As a labor rooted in solidarity, we must look to those with whom we cannot but work and engage in a shared responsibility and shared labor to act more fairly, more responsively and, still, critically in our attempts to achieve understanding and more defiantly oppose a tendency toward foreclosure of meaning, and being. This is a labor that Peter has spent a lifetime performing, and doing so with a host of others, whether like-minded or not, but always together, looking toward a co-created if contested horizon.

Distance, of course, can stand in the way of solidarity. Yet, looking at the map of the contributors to this special issue, we can imagine that the effacement of distance is part of what has made Peter’s work, and his work with others, so powerful, grounded, curious, and endearing. If distance is used to separate a ‘them’ from an ‘us’, then distance stands in the way of the development of our moral selves, of our ability to be for others. Afterall and as the history of colonization has shown, distance, spatial or cognitive, allows an ‘us’ to push a ‘them’ outside of the universe of moral obligations. Peter, alternately, as part of his labors, has practically reduced space, utilizing a variety of technologies to shrink distance, to make the world smaller. Globetrotting, from Melbourne to wherever the American Sociological Association conference was being held, to Leeds, back home, as he chronicles in Intimacy in Postmodern Times (Beilharz 2020b)? From home to Sichuan University, where he continues to traffic in ideas? Zoom? Email? These are and have been staples as he travels, physically and virtually, to traffic ideas and sustain friendships. He also, wittingly or otherwise, bridges the divisiveness that has become the message posted on the walls of borders and boundaries, and our screens. His vision provides an optic where morality, or a utopian hope for a shared world, comes through shrinking space, recognizing interconnectedness, and learning from and contributing to the plurality of it, recognizing our shared responsibility for one another. As Hogan says in this volume about this ethical core of Peter’s vision, he has a ‘humane sense of why we bother about the human condition in the first place. All of Pete’s books emanate how we struggle to give meaning and purpose to our struggles to make our communities and societies better for all its members.’

And here we can draw a connection, and only one of many, between Beilharz and Bauman. In Mortality, Immortality, and Other Life Strategies, Bauman (1992) engages Levinas to consider one’s responsibility for others. For instance, if we think about our relationship to others as simply being alongside them, to simply living in parallel to, then we feel less responsibility toward them. The preposition matters. Being ‘with’ others, alternately, provokes a different problem altogether: In our recognition of them, or our proximity to them, what is our responsibility to the other, and how do we demonstrate it? We can, of course, choose to turn a blind eye toward them, or exercise a responsibility toward them – the dilemma here being whether responsibility toward takes the form of domination over or commitment to. However, Bauman emphasizes that our responsibility cannot require reciprocity – there is nothing the ‘other’ can or must do to ‘prove’ they deserve our care. Conditional responsibility is an intermediary that builds distance, stands in the way of togetherness, and can often become paternalistic – it translates ‘being for’ into being for the one or group who has power, introducing the possibility of an arbitrary division of others who are deserving and those who are undeserving. Such an orientation and its relational dynamics fracture togetherness. Bauman writes ‘[my] responsibility means that the fate of the other depends now on what I do’, and continues: ‘In her version of the Kantian categorical imperative, Agnes Heller demands that I should act as if the alleviation of suffering of every being depended on my action. Only when dedicated to such action, my life counts’ (Bauman 1992: 202). Peter, consciously or otherwise, concretizes these abstractions, exemplifying how we should ‘be for’ others, and not just those we know and come into contact with every day, those who only populate our most proximal milieu. Of course, he is ‘there for’ those for whom ‘distance’ has been reduced to the point of friendship. Yet his everyday life drive, academically, as an educator, is spent ‘being for’ generalized others as well: His work centers on the art of living together, with and across difference, space and time, and his responsibility to all others, ones he has never met and likely will never meet, is unwavering. The catch? There isn’t one, it seems. Peter never expects anything in return, sharing his gifts because he sees it as his responsibility to do so – he is ‘with’ others, a ‘being for’ others.

This Liber Amicorum – The Founding of the Origin Story…

Where and how did this liber amicorum ultimately begin? In teaching-learning, and friendship, as much as it did for Peter himself.

Seventeen years ago, Eric, then a young, high school math teacher, took a keen interest in Zygmunt Bauman as a student in Chris’s master’s-level sociology of education course. Most of Bauman’s available books up to 2010 were on hand and ready to satiate Eric’s curiosity, as were the Bauman studies by Tester (2004), Bauman and Tester (2001), Smith (2000), Blackshaw (2005), Elliott’s collection (Elliot (Ed) 2007), and a seriously defaced copy of Zygmunt Bauman: Dialectic of Modernity (Beilharz 2000). Mentorship became friendship once Eric completed his master’s in the social foundations of education, and then friendship became mentorship again a number of years later when Eric returned for his doctorate and to work with Chris, to the latter’s great pleasure and disbelief.[2] (What’s more, and to our disbelief, this is when Peter entered our fray – he graciously agreed to be an external reader for Eric’s dissertation on Zygmunt Bauman, an account shared in Eric’s contribution to this volume.) We chose to repeat, or return; we chose to do so, even as we changed, as the world changed. It’s not surprising that, in hindsight, Peter’s insights on repetition resonate strongly for us in bringing form to these introductory notes: We got to study, to pick up again, together – same people, same institution, each of us returning, together, but with more maturity, a sharpened set of shared interests, and ever-expanding curiosities, a shared horizon even if seen from different vantage points. Our shared interests in understanding the relationship between schooling and the erosion of democratic life may have shaped our maturation and our interests and curiosities, but so too did our commitments to togetherness, to being for and with others. The horizon remains, as it continues to vanish on approach. So, we try to approach it, as we have returned, again, to friendship. We share this other beginning not to navel gaze, but to call attention to the many ways our separate relationships with Peter influence us, our individual and joint work, how we work, and the heightened attention to care we bring to our work with others.

This work, in your hands or on your screens, thusly emerged out of mutuality, respect, care – friendship – between us, Chris and Eric, and then with Peter and Sian. It is a set of friendships that developed, foundationally, in the process of Peter’s selfless participation – his boundless generosity and radical humility – as the external reader on Eric’s dissertation committee, and his and Sian’s inexplicable, continued care and magnanimous provision of guidance, from 15,000km away! It is a rare care and kindness, exemplified in Sian’s eloquent and affecting recollection of her response to the proposal of this project and her gratitude for our interests in wanting to make it happen, shared here in full:

When Chris wrote to me on 24 July 2023 with ‘an idea’ that he and Eric would like to do a Festschrift in honour of Peter’s 70th birthday and to acknowledge his intellectual work, I immediately said yes.[3] It was something that had been on my mind for several months, but I was unsure how I could do it, so Chris and Eric’s proposal was timed perfectly (if on somewhat of a quick turnaround for authors, and Chris and Eric!). The pieces you are about to read are a testament to Chris and Eric’s incredible organization in such a short time span. They have solicited beautiful and intellectually stimulating works centred on Peter’s oeuvre. I thank the authors for their generosity of spirit in undertaking the task in such heartfelt and critically engaged ways, and on such an assertive timeline.

A special thank you to Chris and Eric. Chris and Eric are ‘new’ colleagues and friends. Eric wrote to Peter, out of the blue in March 2020, much as Martin Jay tells of Peter writing to him out of the blue in the 1970s, to ask if Peter would be an advisor on his doctoral thesis. I clearly remember Peter and I discussing whether he should accept this task. It would be a several-year commitment including regular online meetings, quite a lot of reading and then the final defence panel. We wondered if Peter had time? But as others mention in the pieces gathered here, me included, Peter is a generous scholar and a gracious person. He had no hesitation, and he was intrigued by Eric’s use of Bauman and how he would apply Bauman’s work. He was excited. It was a fortuitous decision. Over these past years the friendship between Peter and Chris has grown and extends to their mutual love of music and Chris’s curiosity about Peter’s work, as you will see in Chris’s piece; and for Eric, the relationship has changed from student to friend, often with exchanges about what’s good to read.

One final thing to say about the extraordinary gift that Chris and Eric have given to Peter, and to all of us. Eric’s defence panel occurred two days after my father died in 2022. Peter and I were locked in hotel/prison quarantine and, due to the 12-hour time difference between Ypsilanti, MI, and Perth, WA, Peter had to do the defence panel around 6am. I was rightly still in shock about my father’s passing, as was Peter, but I remember hearing the voices of Chris and Eric and feeling a sense of comfort. They were kind and concerned and shared in our grief. The very real business of Eric’s defence was important, and we agreed that Peter should continue to be a part of the panel. All this is to say that Chris and Eric have been with us, Peter in particular, now for a few very important life events for us and their families. And we still haven’t met in person! Their kindness, generosity and their own very accomplished intellectual work is a sign that friendship and the academy or intellectual life is alive and well. I thank them both from the bottom of my heart for all their dedicated work on this Festschrift gift for Peter.

And, so we return to gratitude. Among other things, Sian’s words above and her reliable guidance in the production of this collection, along with Peter’s and her ways of being, resolutely oppose the transactional, quid pro quo operations of relational profiteering. We might liken their comportment and commitment to Bauman’s conceptualization of being for the other, others unknown (in this case temporarily). ‘Being for’, in this case, exists as an act of generosity toward another, better yet an unknown other, without the expectation of or desire for reciprocity and, in our particular case, in spite of what life may throw at or take from us (and did take from Sian and Peter). Let’s call it what it is: their true generosity and true humility – genuine tutelage – an almost daily lesson in how to be in the world and how to be for others. Neither of us registered for, much less participated in, a seminar conducted by Peter but, for some reason, he chose to teach us, and he continues to teach us. Only an ingrate would ignore such generosity, kindness, and curiosity.

Conclusion, or, Thank you and Happy Birthday

This, after much ado, was how the ‘Secret Festschrift for a Friend’ began. The idea materialized out of gratitude, along with a deep respect for and appreciation of Peter, the warm person, the masterful pedagogue, and the gifted intellectual. In the middle of active work on another joint project in late July 2023, this tribute idea emerged alongside, truth be told, a panicked awareness that Peter’s ‘Revolution #70’ would be quickly upon us and prospective contributors – at that time, in 3 months on November 13. As the contributions to this layered collection demonstrate, vast gratitude, respect, and admiration duly exist for Peter the Intellectual, Peter the Educator/Mentor, and Peter the Friend/Thought Partner, even if these categories blur and overlap in practice, with Peter, and in the presentation of this volume. Peter Beilharz is Peter B, he is Peter, he is PB, he is Pete, and he is Beilharz, the soft touch, and the ‘stimulant’. What began as a ‘A Secret Festschrift for a Friend’ is indeed a ‘book of friends’ in which the contributors speak in their magnificently varied ways about Peter the Intellectual, Peter the Educator/Mentor, and Peter the Friend/Thought Partner and, in the process, express their gratitude to Peter for the joy he creates for us, on the occasion of his 70th birthday. We thank the many contributors for their kindness toward, curiosity about, responsiveness to, and patience with us in creating this birthday present.

Of course, thank you, Peter, and, more appropriate to the occasion: Happy Birthday, Pal!

Notes

[1] In Thinking the Antipodes, Beilharz (2015) uses the phrase ‘a small country connected by vast distances’ in reference to one image of Australia. See ‘Australia: The Unhappy Country, or, A Tale of Two Nations’, p.39.

[2] While we are committed to friendship, we also are committed to broader values, like institutional integrity, and the role performances associated with them. Chris recused himself from the entire application review process when Eric applied to the program.

[3] We provide Chris’s July 24 email in full:

Dear Sian,

I hope that you are doing well.

While I have not forgotten the gracious and generous invitation you made regarding an edited special topics issue for T11 (in fact, I have actively thought about it since you and Peter surprised me with the invitation back in January), another idea has been bouncing around for me and now Eric, too.

Here is the crux of it, though I’d be surprised if others haven’t already pitched it. Peter has dedicated so much of his intellectual life to exploring, engaging, and bringing attention to other people’s work. On a person-to-person level, he is generous with his time, intellect, kindness, and care. These things are never lost on me. To my knowledge, I’m not aware of any works that engage Peter’s voluminous body of work, including his teaching.

With his 70th around the corner, has anyone recommended doing a festschrift for/about Peter and his work? If not, we’d like to float this idea and ask if you would allow us to helm it or, if you’re inclined, to oversee it with you.

What do you think?

Hugs to you and Peter.

Chris

References

Bauman Z (1992) Mortality, Immortality and Other Life Strategies. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bauman Z (2008) Happiness in a Society of Individuals. Soundings #38: 19-28.

Bauman Z and Tester K (2001) Conversations with Zygmunt Bauman. New York: Polity.

Beilharz P (1987) Trotsky, Trotskyism, and the Transition to Socialism. London: Croom and Helm.

Beilharz P (1992) Labour’s Utopias: Bolshevism, Fabianism, Social Democracy. London: Routledge.

Beilharz P (1994a) Postmodern Socialism: Romanticism, City and State. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Beilharz P (1994b) Transforming Labor: Labour Tradition and the Labor Decade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beilharz P (1997) Imagining the Antipodes: Culture, Theory, and the Visual in the Work of Bernard Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beilharz P (2009) Socialism and Modernity. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Beilharz P (2015) Thinking the Antipodes: Australian Essays. Clayton: Monash University Press.

Beilharz P (2020a) Circling Marx – Essays 1980-2017. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Beilharz P (2020b) Intimacy in Postmodern Times: A Friendship with Zygmunt Bauman. Sydney: Bloomsbury Press.

Beilharz P (2023) Toward the Blues. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Blackshaw T (2005) Zygmunt Bauman. New York: Routledge.

Castoriadis C (1997) Democracy as Procedure and Democracy as Regime. Constellations 4(1): 1-18.

Elliott A (ed) (2007) The Contemporary Bauman. New York: Routledge.

Heller A (1984). Everyday Life. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Seneca LA (1912) On Benefits: Addressed to Aebutius Liberalis (Aubrey Stewart trans.). London: G. Bell and Sons, Limited.

Sennett R (2009) The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sennett R (2012) Together: The Rituals, Pleasures, and Politics of Cooperation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Simmel, G (1910) How is Society Possible? American Journal of Sociology 16(3): 372-391.

Smith D (2000) Zygmunt Bauman: Prophet of Postmodernity. New York: Polity.

Tester K (2004) The Social Thought of Zygmunt Bauman. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wood A, Joseph S, and Linley A (2007) Gratitude – The Parent of all Virtues. The British Psychological Society. Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/gratitude-parent-all-virtues (accessed 10 August 2021).