by Carlo Bordoni

The Italian version of this article was originally published in Il Corriere della Sera

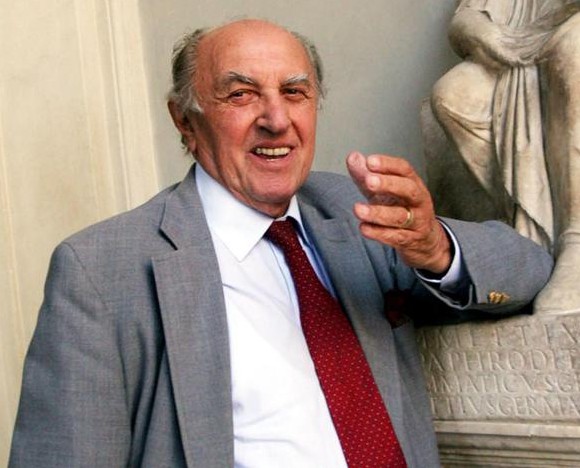

If there are any records in Italian sociology, Franco Ferrarotti (1925-2024) conquered them all: the youngest full professor of Sociology at the Sapienza University in Rome, winner in 1961 of the first and (at that time) only chair in his discipline, which until then was neglected due to the anathema of Benedetto Croce, who had defined it as an ‘infirm science’.

But he was also the founder of journals and degree courses (such as the one in Sociology at the University of Trento), a diplomat, translator, editorial and research director, in the course of a long and incessant activity that has rightly been defined as multifaceted, due to the insatiable variety of interests and aspects he touched upon.

From a peasant family, he was born in Palazzolo Vercellese on 7 April 1926 and had shown his combative nature since his university studies in Turin, where he had studied philosophy with Professor Nicola Abbagnano.

“I was a country boy going to the city” he wrote of himself – “Looking back on it now I almost feel sorry for myself. I had poor health but, like all survivors, I did not lack courage nor did I lack boldness”.

He graduated with honours from Turin in 1949, with an unusual and ‘divergent’ thesis compared to the rigid praxis of those years and for this reason rejected by his supervisor, Augusto Guzzo, immediately to be replaced by Abbagnano, who was more open to the human sciences: with him he discussed the sociological thought of Thorstein Veblen, an author whose The Theory of Leisure Class he had translated for Einaudi, at the invitation of Cesare Pavese.

Unusual, transversal, totally intolerant of rules across his entire career, from his early wartime experience as a young partisan in the Langhe, to collaborator with Adriano Olivetti in the enterprise of Comunità; from passionate scholar and always alien to academic controversies, to deputy in the third legislature, without any party membership cards. But above all he was a traveller.

In almost half a century of our mostly epistolary acquaintances, not once did Ferrarotti not depart or arrive from some journey. He had never stopped since he had graduated and boarded a ship for America. Not as an emigrant, like many from his homeland, but as an observer. Already a sociologist at heart, he wanted to discover, witness first-hand and understand social reality, and to do so he had to get out of the offices, out of the book-lined rooms, and go on location.

Travelling and writing (with a few collateral concessions, including photography, to which the covers of the magazine ‘La Critica Sociologica’ bear witness) were the passions of his life, from his first book in 1951, Premesse al sindacalismo autonomo, to Un greco in via Po (Edizioni Dehoniane) in 2017, dedicated to Nicola Abbagnano, together with the others in the ‘tetralogy of friendship’ (Adriano Olivetti, Cesare Pavese, Felice Balbo) and his most recent books published by Armando Editore in Rome. There were some eighty books and an unknown number of articles.

After the first attempts in the 1940s to publish journals, ‘Progredi’ and ‘La rivoluzione umana: quindicinale della generazione nuova’, Ferrarotti designed and founded the ‘Quaderni di Sociologia’ in 1951, referring to Émile Durkheim’s ‘Cahiers’, with the help of Marian Taylor’s small publishing house. This initiative was soon left to its separate fate (it would be directed by Luciano Gallino), preferring the American experience, despite the contrary opinion of Olivetti and his Turin friends.

Instead, the next journal, totally his from the beginning (1967) and still being published, is ‘La Critica Sociologica’, which celebrated half a century of uninterrupted activity: among the longest-lived of all Sociology journals, and not only Italian.

“I have always had within me the need for a journal,” he admits “to be able to speak to people who are known but also, and even more so, to those who are unknown through a periodical for which I was responsible.” “La Critica Sociologica” lent itself perfectly to the purpose, not only publishing works of great scientific rigour, but allowing him a continuous dialogue in public, intervening on topical issues and keeping alive that critical spirit that has always distinguished his work.

His was a qualitative sociology that eschews statistical coldness and demographic surveys, as well as the academic dryness of specialised studies aimed at insiders. But also he steered clear of the political use of research, from the orders of big industry and markets. Mindful of Max Weber’s teaching, according to which Sociology should not make value judgements so as not to compromise its objectivity, Ferrarotti has always shown himself to be an acute observer, but no less critical. And a bit of a Weberian he has always been, as in one of his most internationally renowned studies, Max Weber and the Fate of Reason (1974), where he deals with rationality, bureaucracy and religion, a subject to which he devoted many works (Il paradosso del sacro, 1983; Una teologia per atei, 1984; Sacro e religioso, From Desecrating Religion to the Homemade Sacred, 1997).

The original influence, the one that has forever marked Ferrarotti’s critical figure, however, remains Thorstein Veblen: the youthful passion, somewhere between anarchic aspiration and social redemption, an expression of love for the United States, a land of great ideals of freedom in the eyes of a young man who had emerged from fascism and, at the same time, a criticism of a nation that, through the conspicuous consumerism of its ‘wealthy class’, had lost sight of the objective of realising the modern utopia of social equality.

Leaving an imperishable testimony of himself are his teaching, of which he was an undisputed master, and his most important texts, including La sociologia. History, Concepts, Methods (1961); Treatise on Sociology (1968), Society as Problem and Project (1979); The Last Lecture. Critique of Contemporary Sociology (1999) and Rome from Capital to Periphery (1970), with a vaguely prophetic orientation.

His example was towering, and his influence will endure.

Biography

Carlo Bordoni is Professor of Sociology at the Universitas Mercatorum in Rome and the co-author of State of Crisis with Zygmunt Bauman (Polity, 2014).