Interview with Matthew Sharpe, translator Domenico Losurdo, Nietzsche, Philosopher of Reaction: Towards a Political Biography, Brill, 2025.

By James Dorahy

JD: In March 2025 your translation of Domenico Losurdo’s smaller work on Nietzsche was published as part of Brill’s Historical Materialism series. The work itself represents a considerable challenge to what has become the received view of Nietzsche. What emerges from Losurdo’s engagement with Nietzsche is an understanding of the latter as a supremely political philosopher, one with a more or less integrated political vision for the transcendence of the egalitarian ethos of modernity. The work then is not merely a significant contribution to contemporary Nietzsche studies; in addition, it can be seen as a polemic against the philosophical and political domestication of Nietzsche as a playful ironist of individual self-becoming. So understood, the organising centre of Losurdo’s work is the rejection of the so-called ‘hermeneutics of innocence.’ Would you agree? If so, would you please elaborate this interpretative strategy, and how it is operative within Nietzsche, Philosopher of Reaction?

MS: I think you have described Losurdo’s project with elegant clarity. Losurdo’s little book, like his larger study Nietzsche, Aristocratic Rebel, aims at a comprehensive rereading of Nietzsche as a philosopher totus politicus. In this way, self-consciously, he is opposing himself to broadly liberal readings, such as Kaufmann’s, which domesticate the many openly antiegalitarian and antidemocratic passages in Nietzsche’s oeuvre. He’s also taking aim at the postmodernist interpreters of Nietzsche, from Deleuze to Vattimo in Italy, who make of the philosopher an artistic, unsystematic thinker, whose main aims were more to provoke and speak almost therapeutically to a small number of outsiders (‘free spirits’), rather than to challenge the egalitarian ethos of modernity, as you admirably put it.

Losurdo’s hermeneutic strategy is in one sense rather traditional, although he is himself a Marxist. He starts by reading everything that Nietzsche wrote, from his earliest writings to the delirium that is already invading Ecce Homo. And he takes Nietzsche seriously, on whatever subjects he sees fit to decree upon.

If Nietzsche writes with horror about the Paris commune, and the ‘fake news’ that the Communards had destroyed the Louvre, it is because he was interested in that, and thought that political events were charged with philosophical and civilizational significance. If he criticises Wagner for becoming a Christian, and for pandering to the modern crowds, Losurdo notes that this criticism has inescapable political valences—Wagner was a socialist, as well as an anti-semite.

By doing this, though, Losurdo the Marxist inescapably situates Nietzsche back into his 19th century context, as at first an enthusiast for Bismark’s second Reich, and then a hostile critic, as Bismark undertook liberalising measures in education but also concerning the growing labor movement of the day.

Nietzsche’s grand history of the clash between masters and slaves, each bearing their respective moralities, is not an apolitical vision, Losurdo highlights. Democracy in its modern form—modern Germany, with its vulgarisation of higher education—represents the liberation of the slave, who the young Nietzsche had already avowed was necessary for a leisured elite to produce the greatest human works. It represents thereby the levelling away of the highest possibilities for the species, up to and including the breeding of new kinds of men to rule over the many; beyond good and evil’. Socialism for Nietzsche is, as it were, even worse than democracy, with its stress on the importance of equal distribution of goods and duties between all members of societies: for Nietzsche, this is madness, which will tame and denature the highest types.

What is needed, as BGE says, is a restoration of ‘rank order’ and with it, less squeamishness about cruelty and even ‘exploitation’ as basic to the human experience in a world without the JudeoChristian God, and the shadows of his egalitarian morality. All of these claims are brought out by Losurdo’s little book; but only because they are nested in the Nietzschean originals, as any reasonably close reading—especially of the post-1883 texts—can confirm.

Let me speak to the ‘hermeneutics of innocence’, which you raise, in the context of the next two questions.

JD: Thank you. Could you then speak to the specific challenges that Losurdo’s reading poses to the dominant approaches to understanding Nietzsche that have risen to prominence since the closing decades of the 20th century?

MS: As I’ve said, the principal challenge Losurdo poses is really to read Nietzsche as we might any other author, aiming at a scientific or comprehensive understanding. To do that, we can’t pick and choose which passages we like, and want to cherish, and excise the rest. At least, if we do that, this rather troubling hermeneutic procedure should be remarked upon and justified.

Losurdo however argues that it is just such an ‘hermeneutics of innocence’ that has come to prevail since Kaufman in many quarters. The term here refers to a hermeneutics that wishes to gentrify Nietzsche, in order that only those parts of his text broadly consistent with the readers’ prior assumptions remain legible. (Losurdo also applies it to Heidegger apologetics around the Nazi commitment.)

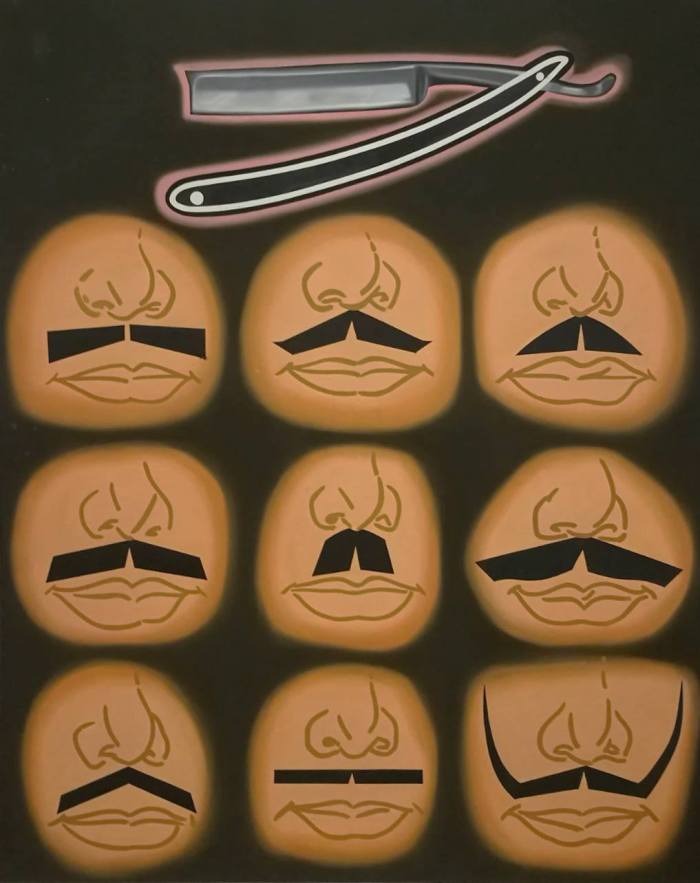

As for the passages that Losurdo highlights which speak to Nietzsche’s advocacy of slavery, open cruelty, exploitation, and even forms of negative eugenics to ‘annihilate’ ‘millions’ of people ‘who have turned out badly’, or in one fragment, ‘entire races’: many students who have been raised on the post-Kaufmannian reception of Nietzsche in the US or Australia will be surprised to actually see that these passages exist at all. But they are in black and white. Neither are they coded by Nietzsche as empty provocations, just to stir the pot. They are attempts to think through in a visionary modality a total revaluation of values beyond the old morality based on the golden and silver rules, which asks us to take care of the weak and to value intrinsic human dignity—not simply for the strong or creative, but for all.

What does such an inversion of the values of charity and respect for human dignity actually look like, Losurdo’s reading gets us to ask? What could it look like? Certainly, as the liberals see, it may involve valorising a certain kind of individualism, at least for the new elites who instrument the civilizational change. But it will also, for Nietzsche, involve what he calls in BGE collective programs of breeding or Züchtung, a word whose translation as “training” is untrue to the German, where it has a biological register. In Antichrist, section 2—how this is missed is amazing, since it is so open—Nietzsche intones that:

The weak and the botched shall perish: first principle of our charity. And one should help them to it. What is more harmful than any vice?–Practical sympathy for the botched and the weak- Christianity…

To be sure, someone will say, Christianity is what is targeted here. But there is politics, and blood, that attends this extolling of a “charity” to help “the weak” to their “perishing”. And for Nietzsche, democracy secularises the egalitarianism implicit in Christianity.

If the only way not to confront the dark political implications of this and many other passages is to ignore them or claim improbably that all such talk—which we agree is troubling—is only a metaphor, we have arrived at the hermeneutics of innocence. This hermeneutics saves Nietzsche for liberal audiences, whose political lifeworld he nevertheless made it very clear he reviled as the overthrowing of the sound principles of master morality, preventing further human achievement. It does so at the price of scholarly rigor in the face of Nietzsche’s oeuvre.

So, this is the biggest challenge Losurdo casts at liberal and postmodern readers of Nietzsche. If our reading of him as an innocent playful artist philosopher depends on hermeneutic suppression and mistranslations which we would not tolerate in scholarship on other authors, there is no need to count Nietzsche out, or give him a free pass. If our readings depend on taking him to be addressing everybody, as if he was an egalitarian, we need to take more seriously his intonings about addressing just “a few, a happy few.” The many are altogether another story, for Nietzsche.

For Losurdo, the vision of a world beyond good and evil that results from Nietzsche’s work has an intellectual consistency and dignity which, paradoxically, some of his best liberal friends have done violence to. We should save Nietzsche as a coherent, dynamic reactionary philosopher from such friends as these. That this reopens the debates around Nietzsche and the Far Right, which liberal scholars have for so long tried to dismiss out of court, is also part of Losurdo’s challenge. And this challenge, I think, is sadly more important in 2025 than it has been since 1945 in Europe and, especially, the United States of America.

JD: I would particularly like to focus in on the legacy of what can broadly be characterised as the ‘postmodern’ reading of Nietzsche. In one sense, the postmodern moment has certainly passed; in another, however, it remains very much present to us. The postmodern is seldom the explicit object of theoretical investigation, only because it has become, in many ways, the very medium through which the present is understood. The postmodern perspective has been institutionalised, not least in the academy. Nietzsche is central in this. Read as a work of cultural politics, then, Nietzsche, Philosopher of Reaction, offers a rather timely intervention – does it not? How do you understand the broader contemporary cultural significance of Losurdo’s reading of Nietzsche?

MS: Well, the debates around postmodernism are perilous: here be dragons, as they say. Its relationship to corporate correctness, as some people have called what the Right calls ‘wokeism’, is also not altogether simple. I do think that the postmodern moment has largely past, except in the imagination of some culture warriors—it seems to me to have been preeminently the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Eastern bloc, a kind of ideological hypostasis of liberal pluralism. The paradox of postmodernism is of course that is presented by advocates and enemies as a terribly oppositional and radical discourse. The reality, as Nancy Fraser among others has pointed out (Thomas Frank is a brilliant satirist of this), is that postmodernism really was very well accommodated from the start to post-fordism, with the individualisation and diversification of consumption, as well as the shift into the realm of culture (marketing, PR) of value adding to products through ‘brand identities’. The culture warriors who worry about ‘identitarianism’ should also rail against the anthropomorphising of ‘brands’ as having specific ‘identities’ or even ‘values’ that employees need to publicly extol. Late capitalist consumerism is identitarian in this sense, to say nothing of ‘race realists’ like we find on the Far Right everywhere these days. And many policies around diversity, and respecting difference, are as you say encoded now into HR policies of big companies, whose avowed purpose remains to maximise shareholder value.

So, Losurdo’s reading of Nietzsche is indeed timely at this moment in all sorts of ways. If you like, postmodernism is a late capitalism friendly Nietzsche, which tries to abstract from concrete politics to denature his radical inegalitarianism, behind extolling his criticism of metaphysical philosophy and his embrace of becoming and difference etc. What the Far Right represents is the return of what liberal readings of Nietzsche tried to repress, the political logic which is encoded into Nietzsche’s world-shaking aims to engender the Overman or ‘complementary man’, or a world in ‘philosophers are legislators’ bringing into being new modes and orders by doing whatever they deem necessary. In terms of the implications of this reading in terms of the institutionalisation of postmodernist countercultural values like difference, recovering a more discerning sense of the philosophies on which these positions are often based—and Nietzsche is usually celebrated and owned—raises interesting questions for the contemporary Left. What if ‘difference’, which we tend to hear as embracing ‘equality’, has been a value imported from contexts and philosophies in which such ‘pluralisation’ is seen not as a marker of emancipation of the lowest or most vulnerable, but one ideological tool which can and has been used—as in racial theory, based on differences alone between groups—as an instrument of oppression?

About the authors

James Dorahy is a Lecturer in Philosophy at Australian Catholic University. He is a co-editor of Thesis Eleven whose research focuses on the philosophical dimensions of the civilizational analysis of Western modernity. He is the author of The Budapest School: Beyond Marxism, published by Brill.

Matthew Sharpe is the author of The Other Enlightenment (2023) and Camus, Philosophe (2014, 2015), and coauthor of Philosophy as a Way of Life: History, Dimensions, Directions (2021) and Zizek and Politics (2010). He has taught and supervised philosophy for over two decades, and is the author of numerous articles in the history of ideas, classical receptions, critical and psychoanalytic theory, continental theory, and Stoic thought. These articles have appeared in leading journals such as Journal of the History of Philosophy, Journal of History of Philosophy, Telos, Philosophy & Rhetoric, Psychoanalysis, Culture, & Society, Journal of Early Modern Studies, Philosophy & Literature, Review of Politics, Thesis Eleven, Political Theory, Continental Philosophy Review, Philosophical Papers, Sophia, Poetics Today, Philosophy & Social Criticism, Philosophy Today, Critical Horizons, New Formations, The European Legacy, Angelaki, Law & Critique. He has also written extensively for The Conversation, and was awarded the 2022 Australasian Association of Philosophy media award.