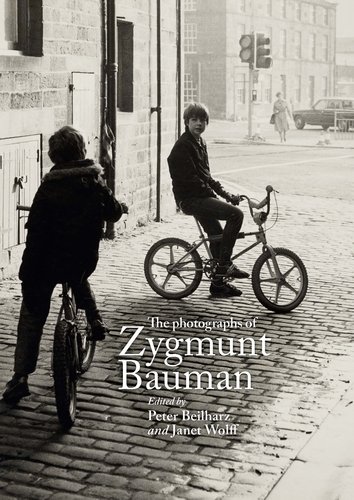

This speech was delivered by Anna Sfard at the book launch of The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman, hosted by Portico Library, 15 July 2023. The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman was edited by Peter Beilharz and Janet Wolff and published by Manchester University Press.

About time: Celebrating in hindsight my father’s affair with photography

by Anna Sfard

More than six years after my father’s death, it was certainly about time to publish this book – the book, which is itself about time, at least for me. Why time? I will explain in a moment. But first, let me share a few memories about my father’s affair with photography.

As some of you may know, Father was a man of passions, of which he had many. Some of his passions were chronic conditions, some other ones – acute temporary afflictions. Because of the long-lived ones, Father sported multifarious identities: he was an omnivorous reader; a devoted cook, a music devourer, a film lover, but above all, a persistent writer, or, as he preferred to self-identify, an incurable scribbler. His other, transient passions made up for their limited lifespan with their intensity. For a while, Father was ardently creating cocktails. Then he started producing his own beers and wines, which we were obliged to taste every so often (and I consider myself lucky to be still here). Before he ceded the responsibility for the vegetation around his Lawnswood house to Charles Darwin, he acted as a constant gardener. And yes, there was the period of photography. Although all he was doing was done with zeal, photography was special in this respect. This craze held his full, undivided attention for a number of years.

As far as I remember – and the Bauman experts among us may wish to correct me – Father’s short-lived passions started appearing in the mid-seventies of the previous century and they gradually faded out toward the late eighties. His infatuation with photography spanned most of that period. I was visiting Leeds from Israel quite often, and from one stay to another, I was more and more puzzled by Father’s new artistic incarnation. It was so unlike him NOT to be up to his neck in verbal scholarly endeavors. Never before had I seen him giving his time so lavishly to any other activity. I found the change fascinating, but also disquieting. One day, when we were alone in his car, Father behind the wheel and I in the passenger seat beside him, I spoke up:

“Why this total immersion in photography? What about sociology, your life companion? Can you be faithful to both?”, I asked.

“Well, no; as a matter of fact I can’t”, he blurted out after a brief pause.

“So what are you saying? Have you abandoned sociology for this new mistress?”

His response:

“Oh well, I have had many good years with sociology, but I think we said to each other all we had to say. It is now time for something new”.

This was a startling confession.

“And there is no way back?”, I continued turning the screw.

Father refused to reconsider,

“I think I’m done with sociology”.

I am reconstructing this conversation from memory, and these may be not the exact words that had been said then. Yet, I think I managed to capture the gist of things: according to his self-report, Father turned to photography because sociology could not any longer be the outlet for his bursting creative energy.

Little did he know at that time about the power of his imagination and wit. In hindsight, I see that photographic decade as an incubation period for his new sociological thinking. When he renounced photography for the sake of his usual medium, the unprecedented, unstoppable verbal outpour followed, and the old platitude “a picture is worth a thousand words” acquired a new meaning. With his characteristic zest, he was now writing about the world in flux. These might well be his decade-long strenuous attempts to document the reality in snapshots that made him painfully aware of how rare a gem solidity became. The world he experienced was available to him only in passing. The world he dreamed about, in contrast, was populated with things, people, and places that stay. He was deeply nostalgic about the stability that his lived-world has irrevocably lost. The slogan “Away with transience” was his guiding principle, indeed, a part of his moral stance. Throughout his life he tried desperately, and rather unsuccessfully, to achieve permanence. He also seemed to believe that what he could not have for himself, was still possible for his children. This chronicler of postmodernity, as he sometimes called himself, insisted my sisters and I should aim at a life of constancy and predictability.

As to himself, well, he had his camera. Within the acutely sensed but as-yet-unnamed liquidity, this little device was his lifesaver. Yes, the camera was his weapon against time and change. By pressing the shutter button, he was able to make the moment stay, and could repeat after Faustus:

The clocks may halt, the hands be still,

And time be past and done, for me!”

Father might have never actually uttered these words, but he did say that photography is – and I am quoting – a “technique of cleansing experience from the decomposing solvent of time”, whereas photographs are “paper-thin, fragile defenses of memory against the winds of time”. Time and photographs co-star as enemies in these quotes, for which I am grateful to Jack Palmer and his essay in this book. All this explains and corroborates my initial point: the book about Bauman’s photographs is also a book about time. Now I can add that by negation, Father’s photographs were, in a prescient way, about liquidity.

It may be interesting to note that Janet and Peter, the team who organized for us this new encounter with Bauman-the-photographer, seem to share his wish to do something about time. Yet, they act on this desire in their own way. Rather than attempting to prevent the time-inflicted losses, Janet and Peter are trying to undo the damage already done. In their efforts to bring back what has been lost, they turn to archives of different shapes and colours. It was in one of those that they found the materials now constituting the object of today’s celebration. But Bauman’s Photographs is not the first result of Janet’s and Peter’s archival expeditions. It was preceded by Janet’s beautiful book Austerity Baby, based, among others, on her family photographs; and by Peter’s exciting Intimacy in postmodern times: My Friendship with Zygmunt Bauman, a memoir that Peter could write thanks to – and I am quoting – “letters; emails; itineraries; plans and projects developments, those powerful “stimulants of memories” that he had been hoarding for years in his drawers. While confessing his love for archives, Peter offered an explanation: “Living across real-time, you forget, transpose, misplace. But I had a record. I had an archive to work with and through.” Photographs, as the most powerful memory stimulants, are a vital part of any such collection.

In short, it seems that the three co-creators of Bauman’s Photographs have much in common: they are all prepared to go a long way to stop time from carrying out its plot. To prevent a moment from passing, Father, like Faustus, would give his soul to the devil. To bring back a moment lost, Peter and Janet, like Orpheus, would rummage Hades-like spaces of various archives. I am grateful to you, Janet and Peter, for your faith in the possibility of bringing lost loves back to life. Let me thank you for reviving some of the moments my father halted. By excavating his photographs, you brought the photographer himself back to life, if only for a moment.

Biography

Anna Sfard is Zygmunt Bauman’s daughter. Based in the University of Haifa, Israel, she researches learning at large, and school learning in particular. Some results of her investigations, in which she conceptualizes uniquely human learning as grounded in the development of discourses, are summarized in her book Thinking as communicating.