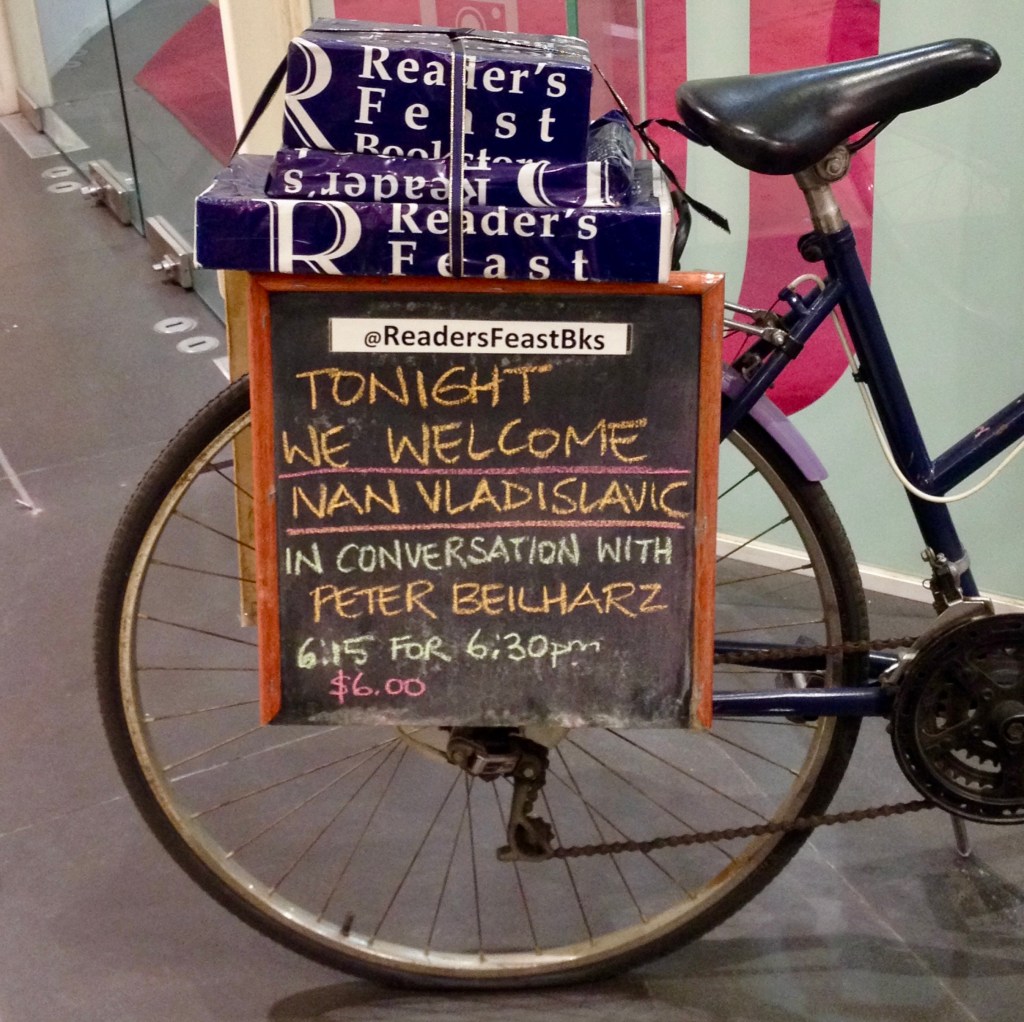

This post is a part of the online special edition Peter Beilharz: The Life of the Mind, Friendship, and Cultural Traffic in Postmodern Times

by Ivan Vladislavić

for Peter Beilharz

21 October

Tram to St Kilda. Minky and I agree it feels like Margate in the 1970s. The beach quite white, the streets dead normal. Except for a kid in camo gear on a bicycle, wearing a German World War II helmet, goggles with popped-out eyes bouncing on springs and a condom on the end of his nose.

Our first free day in Melbourne happens to be Peter’s last teaching day after twenty-six years at La Trobe. To mark the occasion, he wears his modernist T-shirt to work, and we admire it when he comes in this evening with a box of books in his arms. Where will he keep them all now that he doesn’t have an office on campus? The mood around the dinner table darkens when talk turns to Gough Whitlam, who has just died. I must ask Peter what Whitlam means to his generation.

How did the last lecture go?

It was more of a performance than a ‘lecture’. Peter played Marx and one of his colleagues played Weber, and they argued about class and other things. A young woman took issue with their focus on the classic texts. Why bother to read them? You can learn the same stuff by watching The Sopranos – and it’s more entertaining. She was very stubborn about this, which they enjoyed.

This is what the lecture revealed: Peter’s colleague is a classicist and likes to talk about the human condition; while Peter himself is a modernist and likes to talk about contemporary questions.

It’s a good thing you wore the T-shirt then, I say.

He bought the T-shirt in the museum store at the Tate, Peter explains. After finding it on a shelf, he went up to the cashier and asked if they had the same shirt in large.

No, the young man said, they’re all medium.

That’s because it’s a modernist T-shirt, Peter said.

22 October

The early train from Melbourne to Bendigo. At noon, I’ll be speaking to students at the Visual Arts Centre on my work with artists and photographers, focusing on TJ/Double Negative.

On the train, I mention to Peter that I’m anxious about the ‘lecture’. I’m used to readings and panel discussions, the usual festival song-and-dance, but lecturing is not my strong point. If things go off the rails, I say, perhaps we can have a conversation instead?

No problem, he replies.

As it turns out, the talk goes better than I expected. Perhaps because Peter is standing to one side for the whole hour I’m at the lectern, standing by you could say, I can see him from the corner of my eye. He’s like one of those coaches you’ll find near the apparatus when a gymnast is about to perform a risky routine, standing back just far enough not to spoil the effect, but close enough to cushion the fall if it comes.

Peter has arranged a visit to John Wolseley at his studio outside Bendigo. After lunch with Neil Fettling in the café at the Bendigo Art Gallery, we drive out there in a borrowed van. The approach is through a dry, ragged landscape slashed by the trunks of skinny ironbarks like sticks of charcoal. The Whipstick Forest.

The studio is a long, low building with a swayback roof on a sandy clearing in the bush. John and his partner Jenny are helping to unload a large cross-section of tree from a pick-up. It’s Malaysian wood, he tells us once the introductions have been made, very old, perhaps millennia even, and he will use it to make a print. It’s called Dolly Parton – because of its buxom silhouette.

We admire the curves of the roof. It’s meant to resemble a tent, he says, and it was supposed to be suspended on hawsers and sway with the wind, but building regulations and the budget got in the way. It’s a tent, we assure him, no doubt about it.

He takes us inside.

A big space filled with drawings, objects, bits and pieces. Mainly organic things – pods, skulls, leaves, branches, feathers – but also man-made objects and tools, many of them rusted and bent, many obsolete or apparently so. Enormous paintbrushes as long as brooms. Every sort of reject and slough. Things on tables or sheets of paper, pinned to boards, hanging from bolts that stick out of the walls.

While we gape, John offers tea. He steps out into a cluttered courtyard to fill a kettle from a hose that has been stoppered with a piece of wood. When he puts the stopper back, the water sprays all over me. Welcome to the playroom. By way of an apology, I get a bottle of Four Wives Pilsener – or is it Three? Then we potter around on what might be a guided tour, and the artist amuses us by telling stories about himself and his work – his ‘lecture’, he keeps calling it. He heard about my talk to the students in Bendigo and his lecture is to give me a break from speaking, he says, but it’s really an entertaining improvisation on what must be familiar themes. Jenny footnotes his amazing stories about the objects in his studio, how he acquired them and the purposes he puts them to, by saying, Oh no John, that can’t possibly be true! Or, Now you’re making that part up to make it sound better than it is! Or, You can only believe some of his lies.

He keeps fetching things to show us, marching away like a wind-up toy soldier, turning on his heel with a rickety swagger, marching back.

The studio participates enthusiastically in its own invention. Objects proliferate under our curious eyes. As we pass, a photograph drops from the wall where it was pinned. He scoops it up to show us: a butterfly that flew in and settled on one of his landscape paintings. He reminds us about Zeuxis, in the story told by Pliny the Elder, whose painting of grapes was so real the birds came to peck at them.

One of the best routines concerns his illustrious forebears. Here is a picture of Field Marshall Garnet Wolseley, First Viscount Wolseley, who arrived unfashionably late for the Zulu War of 1879. It was his younger brother Frederick who invented the sheep-shearing machine and transformed the wool industry. John has a broken handpiece from such a machine, all hinges and worn rubber, with a part that flaps like a shin below a crocked knee. Also a rusty shearing blade that some admirer sent him. The letter from this admirer is pinned to a board next to a picture of the inventor in his ‘Nietzschean moustache’. He reads out parts of the letter: he was digging a ditch for a sewerage pipe, the sender writes, when he came across the blade. Also: he doesn’t like Art, but he loves artworks by John Wolseley, because they are about something. We all try to fit the blade into the broken shears, laughing and joking, snatching the thing from one another. We’re like oversized, overexcited children with an educational toy retrieved from a midden. Enough of that. We move on to the skull of a wombat. The story that goes with this item is about a brave little boy who used to sneak out at night and crawl into wombat holes. Perilous! John shows us how wombats crush their prey against the roof of their burrow, flexing his knees and arching his back alarmingly.

Later, in need of refreshment, we sit around a table for tea and cake. Minky and Peter sample the fresh mint infusion. I am presented with another bottle of Pilsener in a bucket of ice.

Peter has carried a copy of TJ/Double Negative all the way from Melbourne in a cotton bag. Now he removes the two parts from the slip case, opens the photobook on the table and leafs through it while he describes the origins of the project. As the familiar portraits pass in review, I find myself talking about Chris Killip’s notion of ‘distance’ in David Goldblatt’s work, how he has an instinct for determining the appropriate distance, physical and ethical, from his human subjects. Serious for a moment, John speculates on what this might mean for a painter. Is it a matter of getting closer to the medium? What are the ethics of the painter’s eye? These thoughts spin off into new stories.

When the stories take flight, Jenny brings them back down to earth. Oh nonsense, John, she says. You’ve made this part up. Why on earth would you have done that? You’re just adding this in to make it more interesting …

The ambitious excess of the studio, the tomfoolery and misdirection, as the magicians call it, have brought Willem Boshoff to mind. He’s a kindred spirit, I think. I tell John about the Big Druid’s collections of scissors and walking sticks, and his Garden of Words, which records the names of 15 000 plant species, and other artworks that are immense catalogues of seeds, stones and trees.

In response, he marches away, the unoiled hinges of his limbs cracking, and wheels closer his Herbarium for the end of the millennium, which contains 1 500 drawings of proteacae. And then we are ushered to a corner, where he pulls back a screen to reveal another cabinet of curiosities. Peering through a hole in a wooden panel, I see a painting of a quoll. What’s a quoll? Peter explains. Feathers and pelts protrude from the drawers of the cabinet, as if the furniture has been feasting on living creatures.

Our studio visit is nearly over. But there is something special before we go.

You must see the pelican, he says.

Oh no, not that, John, Jenny says in despair. Please, not the pelican.

But he won’t be dissuaded. We follow him to a large unfinished painting, one in a series about vanishing wetlands, pinned to a wall, a band of paper five or six metres long. It’s an immensely moving, intricate work, simultaneously landscape and inventory of loss, faded map and unstable territory. Among the elusive images of birds are traces of their passage, smears and scratches, feathers. The melancholy mood must be broken. He hauls out the stinking carcass of a pelican, a mess of salty feathers and stringy bones, and throws it on the floor. Sandy crusts fly everywhere. He demonstrates how he paints the dead bird with oils and then flings it on the canvas, laid out on the floor, to make a print.

The bird becomes part of the image, Peter says.

Yes, exactly. It goes back to the medieval practice of painting leaves and flowers and pressing them on paper.

Direct contact. A printmaking mode that collapses distance entirely.

This reminds Minky of the oily smudge left on our lounge window when a pigeon, flummoxed by reflections of leaf and cloud, flies into the glass.

The visit winds down. As he’s ushering us out, John tells the story of Henry and Fritz, who used to prospect in the Whipstick Forest. After long and unrewarding toil, Fritz decided to call it a day. He took a wheelbarrow and a little bag of gold and headed off for civilization. One hundred years later, when a party of hikers stumbled across the rotted barrow and the bleached skeleton, the bag of gold was still clutched in its bony claw. It’s a cautionary tale for prospectors like us, as we go back to the city, empty-handed.

23 October

Breakfast at the Wine Bank. Once a bank, now a B&B and wine boutique. Many things in Bendigo were once something else. Last night we had dinner at Mr Beebe’s, named for the architect of the building the restaurant occupies, first tenanted in 1908 by the Royal Bank. The town, founded in 1851 when gold was discovered, boomed and slumped and boomed again for more than a century, and is thriving now as a service and tourism centre.

After breakfast, we wander through the Bendigo Art Gallery. Then we climb the 124 stairs of the Poppet Head Lookout, a mining headgear built in the thirties and repurposed as a viewpoint. Peter, Minky and I lean on the iron railing. A sidelong glance from Peter: he seems to be enjoying himself. Perhaps he brought us all the way for this, to reconcile two histories. Looking down on what’s left of the mining town, I try to recall the elevated View of Bendigo painted by James Meadows in 1884, which we saw in the Gallery earlier. How am I to know that Meadows never set foot in the town and created his painting from photographs and maps? The views don’t fit together. But all at once now and then dissolve into here and there, and Johannesburg comes into view. For a moment, the places are drawn close together, the bones of my distant home visible under the skin of the present.

Notes on the artworks mentioned in the text

John Wolseley and Linda Fredheim Herbarium for the end of the millennium – Waratah Proteacae (1996) cabinet of various Australian woods containing drawings and watercolours on paper

John Wolseley and Linda Fredheim Reliquary Cabinet for a disappearing species – Eastern Quoll (2001) cabinet of Tasmanian eucalypt containing drawings and specimens of feathers, fur, leaves, earth and rock in metal boxes

John Wolseley Dystopia – the last wetland, Gwydir 2184 (2012-15) watercolour, feathers, charcoal, graphite on paper

James Edwin Meadows View of Sandhurst (Bendigo) from Camp Hill (1884) oil on canvas