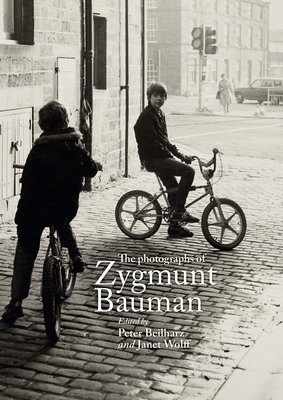

The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman, edited by Peter Beilharz and Janet Wolff (Manchester University Press, 2023)

Reviewed by Eric Ferris (Eastern Michigan University)

(This is a prepublication version of this review. You can find the published version in Thesis Eleven Journal, on the T11 Sage website)

At the end of his contribution to The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman, Karl Dudman paraphrases Bauman, noting that he suggested that “photography inhabits ‘the world … of familiar thoughts and familiar feelings’ and that its meanings are derived more from what the viewer recognizes than what the photographer intends” (pp. 133-134). When looking at the book itself, this idea feels apt for a number of reasons relative to the text, to its contributors, and ultimately to its readers. On one level, the book cannot but look at Zygmunt Bauman the sociologist, approaching his photographs, or photography, film, and other visual media in general, as social texts, albeit in this case mediated through its contributors. It seems to ask: What links his writings and his photographs? Does a formative connection exist at all? What did he want us, the viewers, to see? Or, ambivalently, was there even an object (or subject) that we were supposed to see? Yet these on a whole are our, the reader’s, questions and how we answer them reflects our own positionality, how we anchor them to our familiarity. On a different register, the book is an exercise in generosity. It is also one of remembrance, commemoration, even celebration. Both its longer essays and its shorter personal postcards, most revolving around a particular photograph (or series of photographs), speak about Bauman the parent, grandparent, or friend. Toeing the line between academic and personal, contributors let readers in on Bauman the person. It shares good memories, stories, and congregatings that, borrowing descriptors from a contribution from Antony Bryant and Griselda Pollock, show mutualism, respect, affection, and friendship. All of this generosity comes as a gift to readers who will hold in their hands a text riddled with sociological fodder as well as personal insights into its subject, Zygmunt Bauman, who has likely stirred their own sociological imaginations. It confirms (not that such a confirmation is needed) that the optimism that Bauman had for humanity was not a front, that it was genuine, that he lived it every day, as evidenced in great detail by his friends and his family.

Compositionally, a term fitting for a book concerning itself with the visual, readers are greeted with an interplay between written essay and visual images, many of which were taken by Bauman himself with some notable exceptions being photos taken by Monika Krajewska (around which Bauman’s (1989) essay, “The war against forgetfulness,” was written) and Karl Dudman (whose photos were shot so as to preserve the Bauman’s home at Lawnswood Gardens – as visual anchors for heartfelt memories). The richness of the book’s photos is supplemented, or augmented, with longform essays and shorter “photograph essays”. The longer contributions, ones written by Peter Beilharz, Lydia Bauman, Zygmunt Bauman himself, Jack Palmer, Janet Wolff, Izabela Wagner, Keith Tester, Anthony Bryant and Griselda Pollock, and Karl Dudman, attempt to situate photography (and film) in Bauman’s (and his wife, Janina’s) life and academic career. They explore photography as a way to remember that which might otherwise be forgotten; as a lens that defamiliarizes the familiar. These essays ask the reader to question what they think they see, what they think they know, and contribute to a portrait of an individual who centralized compassion, critical analysis, and respect across his productions. The photograph postcards are written by the already noted contributing authors, but also by others, including Zygmunt and Janina’s children and grandchildren. Contributions from Michael Sfard, Sofia Hepworth, Emi Sfard, Anna Sfard, Hana Bauman-Lyons, Ben Hepworth, Alex Bauman-Lyons, Irena Bauman, and Sian Supski, project the image of Bauman the father, grandfather, and friend, as well as Bauman the teacher, the host, the artist, the sociologist, the reader, the exile, and the optimist in one compelling combination or another. These thought-provoking essays are a celebration of life and love.

The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman is propelled by undercurrents of sociology and social theory. The connection between Bauman’s sociology and photography is present in Antony Bryant and Griselda Pollock’s essay discussing the impact that Bryant’s “showing” sociology at the 1979 “Open Day” at Leeds University through photographs had on Bauman. Likewise, Peter Beilharz’s suggests that photography for Bauman corresponded with and perhaps grew out of a period in which he was disillusioned with mainstream sociology. The connection is further clarified in Jack Palmer’s assertion that distinctions between Bauman’s writings and his photographs may not fundamentally exist at all; both mediums are attuned to, for example, refugees (or strangers) and post-industrial urban decline (the new poor). Lydia Bauman’s photograph essay queries whether Zygmunt Bauman approached his photography with an objective or message in mind, even if, perhaps, he did not fully know what that message was at the time. Elsewhere, Peter Beilharz analyzes Bauman’s photography from a position that both he and Bauman shared – that it, as was the case with his writings, served not so much to answer questions but to pose them. What these and other contributions suggest is that it is not clear where Bauman the photographer ended and where Bauman the sociologist began, if such a distinction even existed at all.

Also, enjoyably, readers are treated to excursus examining Bauman the teacher, shared by those he taught and from those who have learned from him. A reoccurring thread indicates that under Bauman’s tutelage they were always pushed in directions that provoked thought, that they were encouraged to look for implicit meanings, to recognize an artist’s presence in the works they create, and to sympathize with ambivalence. In Bauman fashion, Michael Sfard responds to, or rather reexamines, Bauman’s photograph of a closed gate by asking the reader to consider the history, power, and politics that the image could represent or be informed by: What or who is being let in or kept out? Is the grass actually greener on one side or the other? – all provoking us, the viewer/reader to consider the history, power, and politics that the image could represent or that it is informed by. Another snapshot and essay, this one revolving around a conversation between Bauman and grandchild Emi Sfard about a framed postcard in his house of Salvador Dali’s painting of Jesus on a cross, curiously depicted from above, putting the artist, and ultimately the viewer, in the position of god. The lesson: that the artist is often an unseen subject and looming presence in their own works and that truth is in the eye of the beholder, or in the hands of the creator. Another essay, a recollection by Peter Beilharz, revolves around Bauman’s assigning of films to Keith Tester, his last official student, in which he passes on an implicit and important message: that to the sociologist, the text can be found all around, especially in cultural and artistic productions. From these contributions we gain insight into Bauman’s pedagogical method and the ways that he provoked his students to read sociology through the texts of literature, film, art, and the subject of this book, photographs.

The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman is still an academic book, a sociological text. Readers are reminded of how Bauman engaged with the topic of culture, that culture is praxeomorphic, that actors continually engage with culture to build a semblance of solidity and order. Reflecting one of his favorite short stories, Borges’ “Garden of Forking Paths,” Bauman recognized that the future is not predetermined and holds much possibility; that regardless of where they start, where fate locates them, humans, with their gift/curse of choice, can choose to render it differently, and that it is their character that drives those choices. The book’s essays essentialize the idea that critical sociology sits ambivalently between necessity and possibility, a vantage point that demands that it confronts the fates of our times. Far from the prescriptive sociology of Talcott Parsons, Bauman’s sociology, to borrow from Keith Tester’s essay, lives in and offers up the gray space that is the ambivalence of choice. All that sociology can really do is help individuals make sense of this ambivalence.

The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman also critically engages with its subject. In Janet Wolff’s essay, “Captured by Zygmunt,” she fleetingly speaks to a looseness with which Bauman cited others; that despite parallels in ideas with other interlocuters, their names did not find their way in corresponding reference sections. Furthermore, she reiterates the common criticism of Bauman’s self-plagiarism, even challenging Tester’s sociological hermeneutics defense of this practice. In a separate essay, Bryant and Pollock’s “Gazing sociologically, thinking photographically, deciphering gender,” the authors examine the claim that Bauman never was attuned to feminist sociology or feminist critical theory. In this context they ask why he seemed to prefer to photograph families and women. Their discussion centers on Bauman’s interest in craft photography, a hobby that was itself boxed-in by male photographers, their equipment, and their chemistry. One wonders whether hidden in this commentary is an undercurrent that Bauman should have interacted with photography differently, that even Bauman, as insightful as he was, had his own blind spots. Among other things, and considered alongside the rest of the volume, these essays add to the snapshot of Bauman’s sociology, of course offering up contours to what it might mean to think photographically, but also showing that it is nothing if it is not critical, and that it itself is not above critical engagement.

A cornerstone essay is one penned by Bauman himself: “The war against forgetfulness.” Here, he responds to the photography included in Monika Krajewska’s Czas Kamieni (Time of Stones) (1982). For this project Krajewska and her husband traveled town to town in Poland, searching for hidden, missing, or forgotten graveyards of Polish Jews, ones that had faded into the landscape, out of sight and out of mind, outside of generalized memory. Their objective was to preserve memories of a people relegated to the overgrowth of the landscape, memories of the dead that were purposefully neglected and forgotten. For Krajewska, and later Bauman, the photographs served at least a twofold purpose: for one, to defend memory against the winds of time and two, to be a reminder of murdered talents, lost imaginations, and forgotten beliefs. Without diminishing the importance of Krajewska’s project, The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman itself is a way to remember Bauman, especially for those who knew and cared for him, but also to preserve and reinforce the general memory of him, of his work, especially in times of fast forgetting. It also acts as a blueprint for another way to imagine sociology and introduces an original model for how to “do” sociology.

Overall, The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman feels like a goodbye, a posthumous thank you note, and an outpouring of affection from some of those who were closest to him. It is also a strong sociological text, one that offers readers a vantage point from which they can sharpen or modify their own sociological imaginations. It speaks to method and form in research, or, rather, the pitfalls of latching on to one, the other, or both too firmly. As Bauman the teacher has taught us, text is everywhere and somewhere in our and others’ interpretations of it is a fragmentary composition of how to live together. Or, perhaps, it is these things in this review because they are how this particular read of the book was carried out – appreciative of the humanizing of a sociological superstar, but also looking for new lessons from Bauman through those who knew him best. The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman contributes to our understanding of Bauman the person and spells out the ways that his biography shaped his interpretation of the world, making readers reflect on how their own biographies do the same. It shows us that Bauman, the deeply caring individual who believed in people, was optimistic about the future because of this belief. And it uses this snapshot of Bauman, the photographer and sociologist, to remind us, to recognize our role behind the camera. Specifically, it reminds us, when faming our own shots, to weave in the stories that lie beyond the frame, destabilize our sense of the familiar, and draw our attention to the fragmented narratives that underpin our everyday lives. A book about Bauman’s photographs, yes, but The Photographs of Zygmunt Bauman is certainly more.

References

Beilharz, P., & Wolff, J. (Eds.). (2023). The photographs of Zygmunt Bauman. Manchester University Press.

Krajewska, M. (1982). Czas Kamieni. Warsaw: Interpress.

Author Bio

Eric Ferris is a high school math teacher in Michigan, in the United States, and a graduate from Eastern Michigan University’s Educational Studies Program. He is the author of The (Dis)Order of U.S. Schools: Zygmunt Bauman and Education for an Ambivalent World (2023).