by Rjurik Davidson

‘The King is dead, long live the King!’ This ancient French phrase, dating to at least the Fifteenth Century, is the kind that might have set Fredric Jameson on one of his extended, languorous, alternately dense and playful, intellectually demanding examinations. Marxism’s preeminent cultural critic for more than fifty years, Jameson was the foremost proponent of dialectical thought, in which two seemingly contradictory phenomena were shown to be united by some underlying logic. In this mode, the shells of appearance could be recast as a unity of essence. Originating in Georg Hegel, evident in the young Marx, it is perhaps Hungarian philosopher and critic, Georg Lukács, who stands as Jameson’s most evident forebear. The influence here is not simply intellectual but stylistic. Inherent is a belief that the form of communication is constitutive of its content: the way you write something is essential to what is being written. In this way, Jameson could deploy seemingly irreducibly antithetical and antinomic systems of thought—structuralism and post-structuralism, Freudian psychoanalysis and Sartrean existentialism, Greimasian squares and DeManian discourses—and clash them together in one and the same piece. Arguably, this technique dances along a dangerous cliff: the risk of dissolving real antinomies, producing an eclecticism rather than integration into any coherent ‘totality.’ Is this just a sophisticated way of justifying the use of any old system or approach? If this was the risk, the reward was analyses of striking, often unparalleled, originality.

Jameson’s work is too far-roving, too exhaustively rich and multifaceted, for any individual to fully assess. Who is qualified to assess his extended criticisms of literary realism, modernism and science fiction? Who can both judge his typology of postmodern culture—inspired by Ernest Mandel’s Late Capitalism and roving from architecture to the kaleidoscopic imagery of the digital age—while also weighing his summaries of Marxist literary theory, which launched him internationally, from his masterful Marxism and Form (1971) to his final work, a survey of French intellectual thought, The Years of Theory: Postwar French Thought to the Present (2024)? No sooner do I write these lines then I discover another book emerged this year on the contemporary novel during the crisis of globalisation. Jameson wrote faster than I could read him.

What most distinguished Jameson’s approach was the interaction of two levels: the economic and the cultural. Postmodernism was thus the cultural logic of ‘Late Capitalism’: an incessant commodification of culture and culturation of the commodity. In late capitalism, one bought not simply a product, but an image, a lifestyle, a worldview, an ideology, an old narrative, each typically a reproduction of an older form, returning not parody but pastiche. In this culture, one doesn’t simply buy shoes, one buys this type of shoe, which connotes this thing about itself and thus about you. Nikes or Adidas? One is worn by the greatest basketball player of all time; one was sung about by Run DMC. Ferrari or Red Bull? One will give you wings. PC or Apple? In this commodified culture, each reproduction becomes increasingly unanchored to its original referent, emptying history from the new product: each is like a sheet of paper that has been photocopied and rearranged so many times that the original is indecipherable. This was the culture of the mall, the flashing image, first of television and then the computer. The 1980s was moving into a science-fictional present, which Jameson was diagnosing.

Perhaps the defining visual media representation of this culture was Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), based on one of Jameson’s many literary interests, the work of science fiction great Philip K. Dick. A kind of cinematic representation of the cyberpunk movement, where lone rebels manoeuvred through labyrinthine multicultural streets – think of the combinations of Tokyo and Los Angeles noir, of Hare Krishna marches and lines of lamas passing under neon signs, all set in the shadows of faceless global corporations. Blade Runner captured the enduring interests of the culture: who are we in a world divided between the ‘little people’ and the mega-corporation who may not only own you, but might have built you, constructing even your memories? What is it to be human? Escape is ‘off-world,’ where neither you nor I can afford to go. Gone from this world is nature—at least in the versions of the film before screen-tests suggested an alternate ending (allowing for a series of rereleases, of ‘director’s cuts,’ themselves typically ways or repackaging a film for greater consumption, further market penetration, further recycling of the commodity anew). Science fiction was the genre through which I first engaged with Jameson (who supervised Kim Stanley Robinson’s doctorate on Philip K. Dick before Stan went on to become a SF socialist great himself). Jameson’s Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions—whose central argument he explicated in Melbourne in 2005 for its launch—is one of the defining works of in a field that particularly attracts Marxists. Both science fiction and Marxists have a particular interest in the future; they both typically claim it’s unlikely to be simply more of the same, capitalism version 2.0 and then 2.1 and then 2.2. Something must give. Utopia or dystopia, socialism or barbarism?

For Jameson, however, utopia was unthinkable. This debateable claim may be related to the missing level in his theoretical arsenal—the political. His 1981 The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act is a remarkable work but striking in its lack of any sustained interrogation of the political, despite its title, which some might find a matter of false advertising. This missing category of the political—in the sense of its own autonomous sphere—is symptomatic of a larger issue. For Jameson’s Hegelianism emerged in the context of the American Left in the 1950s and then the New Left of the 1960s, a radical outburst whose recuperated radicalism occurred in a landscape, in fellow Marxist luminary Terry Eagleton’s words, ‘without the impetus or consolation of a militant working-class movement.’ Having travelled to France and Germany in the 1950s, when existentialism was at its height, Jameson quickly returned to the US where, despite the rise in strike activity during the 1960s, radicalism was defined more centrally by social movements—civil rights, women’s liberation, gay and lesbian rights, anti-Vietnam war—and a student militancy that never quite forged a promised student-worker alliance.

The dominant European influences on this generation of radicals (combined with the American current of Thoreau and Emerson) was the Frankfurt school, who had made their way to America to escape the horrors of fascism (though their most talented member, Walter Benjamin, took his own life at the French-Spanish border, having been temporarily refused entry). Born in this intellectual climate, Jameson’s Hegelianism was solidly grounded by his 1971 Marxism and Form: Twentieth Century Dialectical Theories of Literature, which examined mostly this Frankfurt School current: the work of T.W. Adorno and Benjamin, Ernst Bloch and Herbert Marcuse, Lukács and Jean-Paul Sartre (his first monograph was the 1961 Sartre: The Origins of Style). By the 1980s, Eagleton could claim that Jameson’s ‘ruling political concepts, inherited from Lukács and the Frankfurt school, are those of reification and commodification.’ What was missing here? Absent in its first stages was the impact of Althusserian structuralism or Gramscian thought—both of which contributed to theories of literature and culture from powerfully different perspectives to the Frankfurt school. By the time these swept across the Atlantic in the 1970s and 1980s, Jameson’s intellectual formation was effectively complete. His extension would from now on be outward from an established position. So, if Jameson’s interests extended to art and thought of the East and South, to new theories with which he engaged and integrated, this all occurred within the Hegelian-Lukácsian framework. This form of Marxism was for Jameson an ‘untranscendable horizon.’ It was Ernest Mandel the economist that sparked Jameson’s imagination into theorising the postmodern, not Ernest Mandel the critic of Eurocommunism, the defender of Lenin and Trotsky, whose Revolutionary Marxism Today engaged with such issues as dual power, radical movements and the political party, institutions of the State. And so, critics are right to ask: did ‘the political’ on this level—as a relatively autonomous sphere of its own—not also form key co-ordinates for culture and the aesthetic? And does this political influence not make culture and literature also a place of conflict, a battleground of attitudes, in which the films of Ken Loach of Michael Moore clash ideologically with those of Clint Eastwood or Dinesh D’Souza? Art is not reducible to politics, of course; neither is it independent of it.

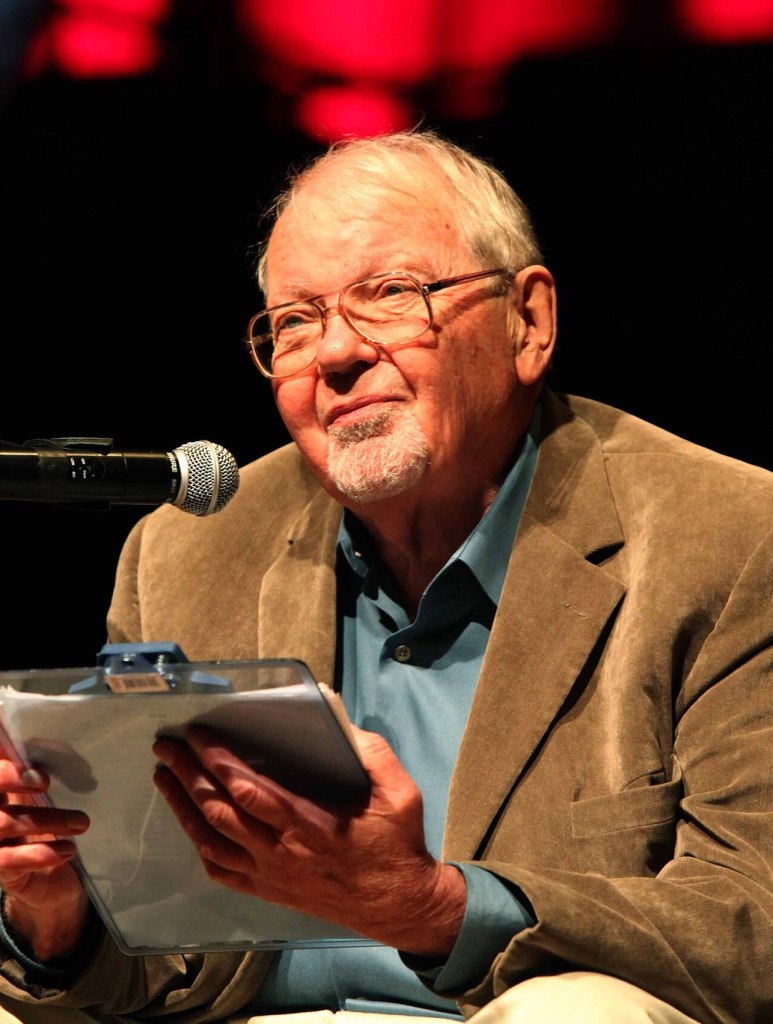

Jameson seems never to have adequately confronted this lacuna of ‘the political.’ Rather it was theorised and justified in his book on postmodernism (Perry Anderson notes this dynamic in The Origins of Postmodernity). Perhaps the argument is rejoined in one of Jameson’s more recent works— here I plead ignorance and gesture somewhat shame-facedly to Jameson’s prolificity. But if not, and this more likely, the silence seems to me the dialectical underside of Jameson’s undoubted strengths: a sustained and unremitting examination of the interrelations of economics and aesthetics. The silence on one side is in proportion to the achievement on the other—in true dialectical fashion of which Jameson might approve. To reification, commodification and totality, we should thus add contradiction as a decisive Jamesonian category. And so it is that ‘The King is dead, long live the King!’ is not only reminiscent of Jameson’s thought and style but an appropriate epigram for a farewell. Jameson, master of cultural criticism, died on 22 September 2024. His work will live long.

This article was first published by the Red Ant Collective. It is republished here with the permission of the author.

Hi RjurikVery good piece

LikeLike

Pingback: Fredric Jameson (1934-2024): Debates, Memories, Obituaries – Serdargunes' Blog