by Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson

Terry Smith in Ian McLean, Terry Smith, Darren Jorgensen and Sam Beard, ‘Doubled Histories: The Futures of Australian Art’. Dispatch Review Special Edition, December 21, 2023… Our polity here in Australia remains riven by the doublings between our Anglo-history and Indigenous history. Reconciling these two unequal formations – not so they merge, but so that they coexist – has been hard. Some progress has been made. More, I hope, when the ‘Yes’ vote prevails in the upcoming referendum.

A significant moment occurs towards the end of Ian McLean’s A Double Nation: A History of Australian Art (2023). In almost the last words of the text, with Australian art “moving towards a new sense of itself”, McLean writes that his narrative has comes to an end: “This [idea of Australia moving towards a new sense of itself] is a story for another book, and one in which the reverberations of Imants Tillers’ post-national ‘aesthetic epistemology’ are strongly felt, most notably in the art of Gordon Bennett”. But several pages before that, following the example of art historian Francis Pound, who stopped his 2009 history of New Zealand art in 1970 when it became “post-national”, McLean admits that, properly speaking, his own narrative also ends in the 1970s: “Double Nation tracks a similar timeline. A national self-consciousness first conclusively appeared in Australian art after the First World War, though, as Double Nation does, its gestation can be traced to colonial art. A line is drawn under 1970 because by then new generation artists were making sharp turns away from the national imperatives that helped shape Australian art during the previous fifty years”. Of course, if we wanted to generalise, we would say that the period after the 1970s – with the decline of the designation post-modern – is called the contemporary. It is the contemporary now that is understood to come after the modern. So that McLean can be seen as suggesting – or conceding – that Double Nation is not able to relate a history of the contemporary because this would be the task for another book. One in which it would no longer be a matter of a “double history”, which if we wanted to summarise here would be that division between white and black, the national and the non-national. One in which they might finally come together in some long-awaited reconciliation. But it is a reconciliation that is deferred and has not yet been written, and perhaps cannot be written, because otherwise McLean would surely have written it. (It is not a personal admission he is making here, but as though the method or moment is not yet upon us.)

However, if the contemporary means anything, it is not only the overcoming of the division between white and black and the national and the non-national, but also not a matter of some simple chronological passage from the modern to the contemporary. If the contemporary means anything, it is not the next art movement – that kind of chronological progression is the modern – but has always (we are tempted to say retrospectively, but that is not true) been the case. All art history is contemporary and always has been. So, in one way, we are tempted to ask, what status and explanatory power does McLean’s art history have if it cannot explain our present and how we got there – this, of course, would be the orthodox historical objection – but undoubtedly the more challenging question is, if the contemporary is a contestation of this progressive, teleological conception of history, why is the contemporary deferred towards the end of the book, why is he not already writing a contemporary history or a history of the contemporary in Australian art? Which is to suggest that the history McLean writes is not the real history of Australian art, insofar as it cannot explain how we got to where we are today, and is not a real history of Australian art because it is not a contemporary history, which it always (again, we are tempted to say retrospectively, but again that would not be true) has been.

This “contemporary” that we say is missing from McLean’s Double Nation is a complex and difficult-to-think proposition or let us say hypothesis or even let us say – to complexify and confuse everything – doubling. Of course, virtually all art-historical thinking of the contemporary sees it simply as a sequential period, one that comes after the modern. We find this, for example, in Charles Green and Heather Barker’s recent When the Modern Became the Contemporary: The Idea of Australian Art 1962-1988 (2024). We see it in Terry Smith’s What is Contemporary Art? (2009), where, if not strictly sequential, the contemporary is one of several alternative ways of understanding the present, between which we can apparently choose. But what we absolutely want to contend is that, if the contemporary is anything, if it possesses any distinctive qualities of its own, it has always been the case and forces us to think that it has always been the case. (Of course, there is a kind of division here between the contemporary and where we think it from, but it is not the same division as we see in McLean’s “double nation”, and we will come back to this.) And art historians do indeed hesitate before this “contemporary”, not knowing where it will lead them. That the future is already with us and always has been. That the past, present and future co-exist in a different, non-modern, non-chronological conception of time. This is Peter Osborne in his Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art: “The contemporary projects a single historical time of the present, as a living present: a common, albeit internally disjunctive, present historical time of human lives”. It sounds like the kind of time Stephen Gilchrist made the subject of his 2016 – needless, to say, that date must now be seen in inverted commas – exhibition of “contemporary” Indigenous art at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia: “The Dreaming does not merely preserve the past. Rather, it speaks of eternal becoming. It is the totality of Indigenous knowledge and its future potential, made alive through its immediate and continuing transmission”. It also sounds like what Archie Moore says was the basis of his Golden Lion-winning kith and kin at the Venice Biennale: “The archives keep our present in our past and future, just how the Aboriginal temporal system dictates everything always is, always was and always will be”. And it even sounds like what D’harawal scholar Bronwyn Carlson means by “Indigenous Futurism” in her ‘The Future is Indigenous’ in The Routledge Handbook of Australian Indigenous Peoples and Futures (2023).

Let us go back to McLean, without doubt the most important historian of Australian art writing today. There is a profoundly consistent logic to his work that led up to that moment in Double Nation where he admits that he is unable to complete his history of Australian art, when the logic of the “double” or the “double history” no longer applies. For much – or let us say exactly half – of his previous work has been characterised by that same double logic, that same hinted at but endlessly deferred and perhaps even impossible reconciliation between white and black and the national and non-national. In 1998’s White Aborigines: Identity Politics in Australia, McLean’s argument is that the work of white settler artists is absolutely driven by the desire to reconcile with the original inhabitants of the land they had stolen/occupied, to become in effect Aboriginal: “When, after the First World War, Australian impressionist paintings achieved their greatest popularity and became emblems of a nation, non-Aboriginal Australians began to consciously assert a white Aboriginality, and the mantle for the redemptive vision passed, as if by natural descent, from Streeton through Hans Heysen to the Aboriginal painter, Albert Namatjira”. And, reciprocally, in 2016’s Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art, McLean argues that the work of Aboriginal artists arises in response to the occupation of their land by its invaders/colonisers, that their work is an attempt in some ways to converse with and even become them: “Mimicry is a principal poetic means by which Aborigines become other – be it the mimicry of various real-life actions in corroborees or Bennelong’s mimicry of British manners. Similar spontaneous improvisations occurred on a regular basis when the Aborigines imitated the colonists, seemingly for the fun of it”. And altogether this “doubling” – first of all between white and black, but we would also say as a consequence of this between the national and non-national – runs all through McLean’s work (actually again, in a way we will come back to, exactly half). Other of his books also have the word “double” in their titles – the edited collection Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous Contemporary Art (2014) – and similarly the word or notion “doubling” and its accompanying “reconciliation” or failure of “reconciliation” occurs in any number of passages in his work. Take this excerpt from ‘Postcolonial Traffic: William Kentridge and Aboriginal Desert Painters’ (2003): “If many Australian desert acrylic paintings look like contemporary modernist abstraction, they have not been assimilated into either contemporary or Australian art – and will not be until the stories of contemporary and Australian art are radically changed and some form of political and social reconciliation is actually achieved”.

How to think the limits to this? How to speak of its other, beyond and, more tellingly, after (which is also its before)? Perhaps, to begin, we might consider the arguments that have been made against it in terms of its characterisation of Indigenous art. This is Ann Stephen in her review of Rattling Spears, pointing out the limits of its thinking the art of Aboriginal people arising in response to their colonisers, as in effect national or “Australian”: “Subsuming all Indigenous art after contact as modernist was always going to be a minefield and McLean does not shy away from the combat… His Indigenous pantheon that constructs an alternative modernist canon based on race continues to frame the exchange in European terms, even if deemed ‘performative’ or transcultural, shoehorning diverse Indigenous forms into a linear postcolonial straightjacket”. But two things already complexify this criticism, in fairness, which point both to the difficulty of thinking outside of this paradigm and the possibility of doing so. First, we might suggest that, for all of her criticism of Rattling Spears for thinking Aboriginal art as arising in dialogue with white Australia, this is in fact no different from Stephen and Ian Burn’s ground-breaking 1992 essay ‘Albert Namatjira’s White Mask’, in which they suggest that Namatjira’s work arises within Australian art, is some kind of response to or appropriation of it (and, indeed, at one point in their essay they even refer to Namatjira’s “double vision”). Alternately, we also have to acknowledge that at other moments of McLean’s work he does want and is perhaps able to think Indigenous art outside of its relation to white Australia, as in effect global and global from the beginning, before European Australians arrived here: “While not influenced in any obvious or meaningful way by Western modernism, their struggles also opened onto the primal bedrock of visual language… before the Babel of iconography and semiotics took hold”. Equally, there are also moments where, for all of his characterisation of white settler art as engaging with a prior Aboriginal presence in order to produce a “national” art, McLean attempts to think Australian art in the context of the global, breaking with the “Australian” in what we might even call an “UnAustralian” art. And likewise this would be a possibility that occurs not at the end of Australian art history but from the beginning, even making Australian art history possible. This is McLean in his ‘The Necessity of (Un)Australian Art History for the New World’: “In many regards, the current developments of globalism and Aboriginal art revisit the crisis of definition that both founded and nurtures Australian art. Hopefully, rather than replay it they cut back to the frame of Australian art history”.

Can we, as it were, invert the art history McLean relates in Double Nation and suggest that this “contemporary” Australian art occurs not at some period towards, actually after, the end, call it the 1970s, but at the beginning, before so-called “Australian” art history, and not disappearing when this history starts getting written, but remaining throughout, making it possible? That our national history, in fact, arises in response to and attempts to repress this contemporary? And that Australian artists – some – and Australian art historians – almost invariably – knew of this UnAustralian history, but sought to deny it, pretend that it had not already happened? It is exactly the story of ‘Exodus’ and ‘Leviticus’ that Bernard Smith tells in Australian Painting, but written not as it usually is as the shame of returning after a failed exodus, but as the returning to shame oneself in the national after a successful exodus. It is the story of Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Margaret Preston and even Smith himself coming back to make a national art after first encountering the non-national. It is even the shame, we might say, of Smith writing the nationalist Australian Painting in 1962 after writing the transnational European Vision and the South Pacific in 1960. And it is the shame of thinking Aboriginal art and culture arising in relation to settlers/colonists/invaders, as though it needed to be named and recognised by some Other. In fact, as with the history of UnAustralian art that we are attempting to write, we can imagine a new history of Aboriginal art that demonstrates that it is not just global and out in the world now (Kngwarreye in Japan, the Steve Martin collection, the Kluge-Ruhe Museum), but always has been before “Australia” was even thought about. Undoubtedly, others are much better equipped than we are to write this history – and we look forward to them doing so – but among the inspiring and initiating books and essays we have come across are Wilfried van Damme’s ‘Not What You Would Expect: The Nineteenth-Century Reception of Australian Aboriginal Art’ (2012), Susan Lowish’s 2004 PhD thesis ‘Writing on “Aboriginal Art”, 1802-1929’, which she later turned into her 2018 Rethinking Australia’s Art History: The Challenge of Aboriginal Art and Marcia Langton and Judith Ryan’s recent 65000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art, although we are tempted to retitle it 65000 Years: A Long History of UnAustralian Art. And we would point to such crucial moments in the global reception of Aboriginal art as the sending of a shell necklace and string basket from Tasmania to the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, the display of Dja Dja Wurrung cultural objects in the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the collection and exhibition of Indigenous material during the interwar years by the Surrealists, particularly Paul Éluard and André Breton, the remaking of Wandjina cave paintings for 40000 Years of Modern Art at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1948 and the exhibition Aboriginal Art at the existentialists’ bookshop-gallery of choice, La Hune, in Paris in 1956. It would be an UnAustralian and perhaps even “UnAboriginal” history of Aboriginal art (and, indeed, any number of Indigenous artists have already spoken of the inappropriateness of the designation “Aboriginal” to describe the art and culture of First Nations peoples.) And the absolute equivalent of the presence of Indigenous cultures out there in the world not needing any recognition from white Australia is their millennia-long intersection between and influence upon themselves before Europeans arrived. Put simply, Aboriginal art was transnational from the beginning. Here we might point to the current hang of Indigenous art at the National Gallery of Australia, where, beneath Fiona Foley’s Dispersed (2008) high up on the wall there is an emphasis on, as the didactic panel puts it, both “trade, cultural exchange and relationships with neighbouring clans” and the “long history of trading relations and encounters by sea between First Nations Peoples and other countries”, including Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, China, Japan, Holland and Spain, before the British arrived and colonised. (And we realise that Foley’s Dispersed is about the attempted genocide of Aboriginal people, but this other reading of the work also points to the fact that they were unable to be “dispersed” because they lived beyond the reach of their colonisers.)

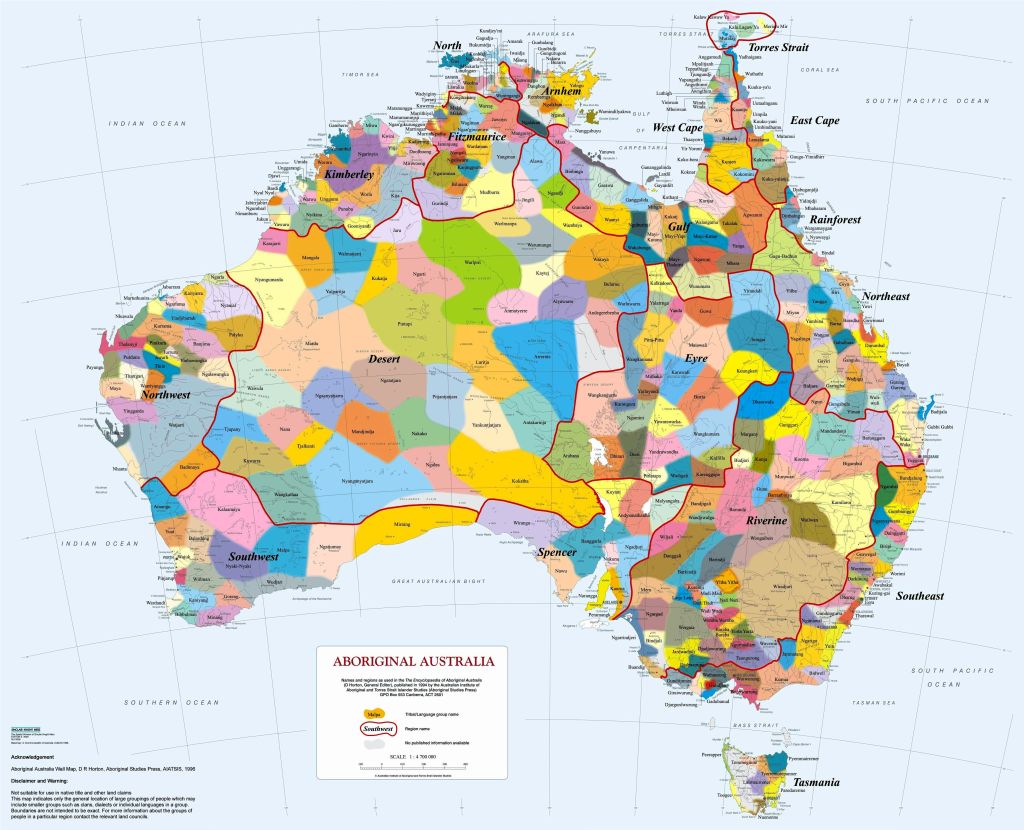

In a doubling and polemical way, we would want to say that what a proper telling of our history would reveal is not a reconciliation between white and black Australians that has not yet happened and is doomed to fail, but one involving all the colours in between that has already taken place. (And one profound expression of this is that wide spectrum of colours that marks the some 250 language groups and 500 clans or tribes of the AIATSIS map of Australia.) Aboriginal art and culture has not needed a white Australian referendum in order to be acknowledged. It has already happened out there in the world. The contemporary UnAustralian has taken place from the beginning, and, besides, Australia is the very name for the impossibility of reconciliation between black and white. (And if we wanted to imagine their “co-existence”, it would not be in the name of a “double” history, which must always seek their coming together and would end when this no longer seems possible.) The UnAustralian is strictly the equivalent of Howard Morphy’s suggestion that “Australian art would be seen… as one stage in the history of Aboriginal art”, although again why not think that this has already happened?

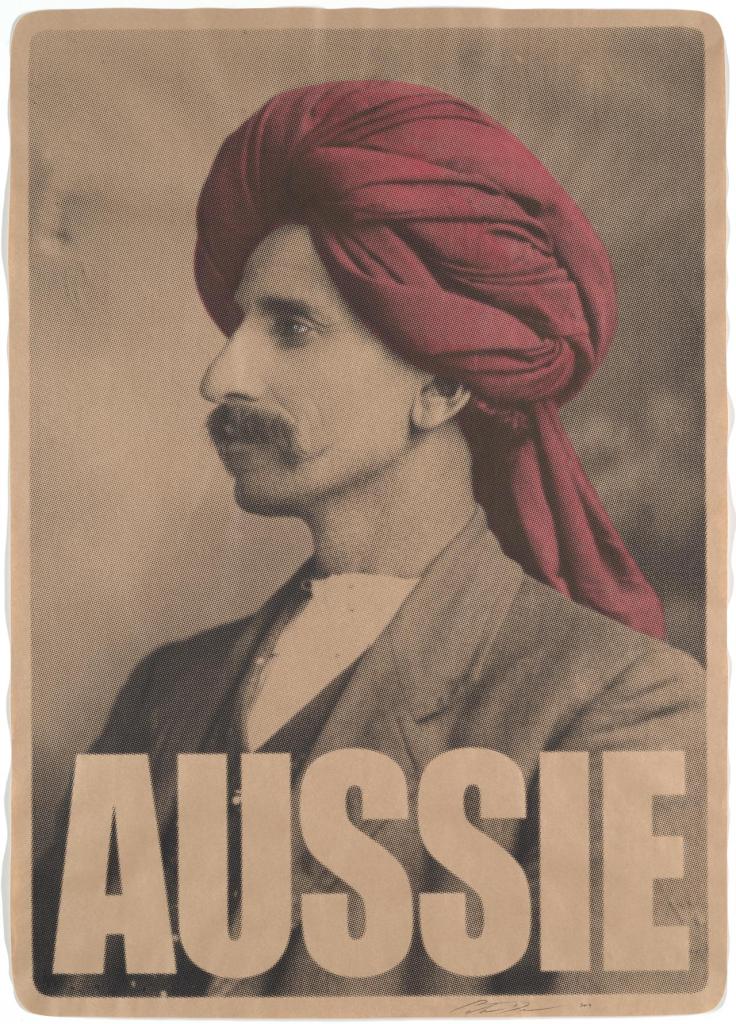

To summarise and to get towards a conclusion, Darren Jorgensen in his generous, heartening, get-you-thinking and got-us-thinking review of our UnAustralian book suggests that this “new” UnAustralian history would be a “complement” or “parallel” or even something of a “double” of the existing histories of Australian art, as though it is added on, completes or even – to return to that moment of McLean’s book that we began with here – comes after these histories, and as though it were actually new. In fact, as we want to keep on insisting, this so-called “new” UnAustralian art history does not arise as some more inclusive, post-colonial, post-national challenge to the existing histories, but comes before them, making them possible. There has, of course, been an Australian art history and there undoubtedly still is one, as McLean’s book shows us, but it arises only as an inflection, a moment, a necessity, a fantasy, within the UnAustralian one. How? We have spoken of a contemporaneity that has always been and is, as it were, the stopping of modernist time, the coming together of past, present and future. We have spoken of a decentring of world art, a flattening, horizontalisation, non-hierarchical globality, in which no country or culture is isolated, in which immigrants and expatriates count, in which there are nothing but scenes, stories and coincidences. (And, speaking of coincidence, just over the road from where we are speaking now, the State Library of Western Australia has an exhibition entitled Sheiks, Fakes and Cameleers about the some 4000 camel drivers from Egypt, Iran, India, Turkey, Syria, Afghanistan and what is now called Pakistan who came to Australia between 1870 and 1920, the photos of whom cannot but remind us of those wonderful Monga Khan “Aussie” posters we see pasted up around our streets.) It is the fact that, as we never tire of reminding people, Margaret Thomas, Edith Fry, Jack Lindsay, Douglas Cooper and Mary Cecil Allen were already writing non-national histories of Australian art in the early twentieth century, that John Russell passed on Monet’s lessons to Matisse, that Martin Lewis taught Edward Hopper and Wallace Harrison taught Helen Frankenthaler, that David Smith was influenced by rarrk painting, that Forest Bess tried to become Aboriginal, that Joseph Beuys incorporated boomerangs into his work, that Sol LeWitt’s late work is heavily indebted to Emily Kngwarreye, that Charles Basing painted the ceiling fresco of New York’s Grand Central Station, that Braque, Mondrian and Giacomo Balla all painted gumtrees, that Alexander Calder and John Skeaping sculpted kangaroos, that Bjarne Melgaard and Julian Schnabel both painted platypuses, that EA Hoppe had a worldwide bestseller on his hands when his photographic survey of Australia from East to West, Funf aus Funfter, was published in 1931, that Charles Conder participated in the inaugural exhibitions of Samuel Bing’s Art Nouveau in Paris, that Gordon Coutts entertained fellow artist Winston Churchill at his Moroccan-inspired villa in Palm Springs, that Polish artist Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, aka Witkacy, produced numerous Australian Landscapes (1918) following his time in Australia on an expedition to the Pacific with the anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, that Horace Brodzky was producing book covers for the first editions of Eugene O’Neill in America in the early 1920s and that Fred Schonbach was doing the same for the first editions of Jorge Luis Borges in Argentina in the early 1950s, that unknown to Australians until only last year Sheila Legge and Mary Low were creating Surrealist performance, Surrealist collage and writing Surrealist poetry in the 1930s in Europe, that Indigenous objects, including churingas as well as barks, are part of the gesamtkunstwerk that is Breton’s bureau wall, now on permanent display at the Pompidou, that Brancusi’s great muse Margit Pogany, a refugee in Melbourne after the war, could not sell her treasure, a bronze version of herself by the great Rumanian sculptor, to the NGV because they did not understand what they were being offered, that Percy Grainger not only made a contribution to sound art when he constructed his experimental Free Music Machine in 1948, but thereby also made a remarkable yet invisible contribution to sculpture in Australia, that before and after her trip to Australia the American minimalist Anne Truitt made sculptures in homage to this country, that Sigmar Polke smuggled yellow cake out of the Northern Territory and kept it in a lead box in his studio for the rest of his life and generated works using its radioactivity to produce imagery. We were never provincial. No one really believed that about ourselves. It’s an art historian’s fantasy, just like “Australian” art, not shared by artists – and our UnAustralian history is unapologetically Ian Burn’s artist-centric one. Not only did Burn himself co-curate the inaugurating Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects at the New York Cultural Centre some four years before Terry Smith published ‘The Provincialism Problem’ in Artforum in 1974 and Robert Hughes review Robert Hunter in Eight Contemporary Artists at MoMA in Time two months after the article appeared, but also in Artforum some three issues later Elwyn Lynn – notably an artist – had this to say about Smith’s piece, writing of two Australian artists who had recently had international exhibitions and been written about in Art International: “It suggests that when the provincials are overtaking or jogging alongside the metropoles, there is something wrong with the training methodology”.

But where to think this UnAustralian with its end of history and absence of boundaries from? This is a problem that has begun to be thought with the notion of so-called “standpoint aesthetics”. From where do we narrate the history, or at least the story, of all of this? How do we become aware of this immersion, this immanence, this involvement? We have to think and speak it from somewhere else. And this would be the “double” in our double history: not the split or complementarity or even parallel between the national and the non-national, as though awaiting some future resolution or reconciliation, but the fact that each time we can only tell another story of “Australia”. For our UnAustralian history is always located, is always particular. It is always – to return to Burn’s artistic-centric history – a story of particular scenes, locations, events. It is not an empty, universal view upon ourselves – that is more what we find in those globalist, survey-like histories of the contemporary, which are secretly universal and modernist, pretending that they can look on at the world from some undeclared and unacknowledged place. In fact, not everything counts in our “UnAustralian” history. We had originally thought that our artists, curators and historians, if they emigrated, had to have been more than born here – that is why, for example, we did not include EA Hornel or Édouard Goerg – but now, admittedly, we have told the story of the art historian, collector of Cubism and lover of Francis Bacon, the extraordinary Douglas Cooper, even though his family left Australia before he was born. Nevertheless, not everything will count as “UnAustralian”. If ours remains an “Australian” history, if we can only continue to speak in the name of Australia – and this would be that proper logic of “deconstruction” often evoked in relation to the new histories of Australian art – it can only be explained because of, it only arises in reaction to, the “UnAustralian”. The national is a rejection of the non-national. It is the non-national that comes first and makes possible the national. So that, if we were to draw something of an opposition, we would say that, if McLean’s history is finally an “Australian” one that can be explained only because of the “UnAustralian”, our history is an “UnAustralian” one that can be narrated only from the point of view of the “Australian”. This is why we can read McLean’s work – we are tempted to say exactly half – for its repressed unacknowledged moments of the non-national (for example, the work of the Post-War School of Paris expatriate Mary Webb in Double Nation, or the connection between Indigenous Australian and Black American activism in the 1960s he spoke of at its launch). That typical chronological structure of ‘Empire’, the ‘National’ and the ‘Post-National’ we see in his work could be rewritten to make ‘Empire’ the pre-national, the ‘Post-National’ as continuous with it and the ‘National’ as the momentary effect of a non-national that runs beneath it, making pre- and post-national the same. And for our part “Australia” is that perspective from which we observe the inter-connection of all parts of the world, including Australia itself. We might draw an analogy to Bernard Smith’s European Vision and the South Pacific, which has been a constant inspiration for our work. Of course, the book is a great trans-national history, showing first the movement of Neo-Classical ideas and images from Europe to Oceania and then its reversal as Romantic ideas and images move from Oceania to Europe. But where is this observed from? From where does Smith write his “UnAustralian” history? From the point of view of a certain “Australia”, indeed, we are tempted to say Indigenous Australia, looking on.

UnAustralian art is the art of our present, those missing years since 1970 in McLean’s book. But the real point – to say this for the last time and to conclude – is that we have always been like this. It is simply not true that, as McLean says of Double Nation: “My other rationale [for Rattling Spears and Double Nation appearing separately] is that the single volume history that I believe is necessary is still too difficult to imagine”. This history has been written for a long time, just not in the name of “Australia”. Those stories we tell of immigrants and expatriates from the past read as though they could have happened yesterday, and we can identify with them as if they were ours. We are all first of all non-national, non-Australian, So many of us, nearly all of us, are immigrants. Quite a few of us have been expatiates. This unmodern, unAustralian history is the story of our present, but, of course – this is the true lesson of history, if we still believe in it – it has been this way forever. Otherwise, how did we get here? It is the “anywhere” of the contemporary in Osborne, the “everywhen” of past, present and future in Gilchrist and the “archive” of the past in our present and future in Moore. We do not have to wait for some official “reconciliation” for our doubles to get together in some far distant time. The future has already arrived, and has been with us forever. We just have to write it and think it, and we already have. The present, the contemporary, the years after 1970, are all around us. It is tempting to wait another 50 years when all this will be accepted, when all this will come to pass, but that would be hubristic, as though we in the present were the first to think this, as though it all started now. Really, the point is – and this is the kind of “history” we have tried to write – if any of this is true, it has always been the case and others have already thought and written it. Before us there was Edith Fry and the two exhibitions of the group Australian Artists in Europe she mounted in London in 1924 and 1925 in response to Sydney Ure Smith’s nationalist Exhibition of Australian Art, held at Burlington House in 1923. There was Dharung man Anthony Fernando, who could be found at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park in London most weekends in the 1920s with toy skeletons pinned to his coat asking “What have you done to my people?” Or the French explorer François Péron and his description of “rudely engraved” Tasmanian bark painting in his Voyage of Discovery of 1802. And here we would add all the UnAustralian histories written by Australian art historians, critics and curators about the art of elsewhere, unconcerned in their work to reflect on our national characteristics. We might think here of Mary Cecil Allen and her Mirror of the Passing World (1928) and Painters of the Modern Mind (1929), published in America, and before her Margaret Thomas, whose How to Judge Pictures (1906) and How to Understand Sculpture (1911) were popular in Britain before the First World War. All of these moments belong to any proper history of “Australian” art, and anyone who is interested in them, who makes them part of their national history, say British or French or American history, is Australian too. This is what makes us all UnAustralian. We invite others to join the conversation.

This is the text of a lecture originally given on 7 September 2024 at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, on almost the first anniversary of the failure of the Voice referendum. The authors would like to thank Sam Beard and Dispatch Review for hosting the lecture. We would also like to thank the three respondents to the original lecture, Peter Beilharz, Tara Heffernan and Darren Jorgensen.

References

Bronwyn Carlson, Madi Day, Sandy O’Sullivan and Tristan Kennedy (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Australian Indigenous Peoples and Futures, Routledge, 2023

Stephen Gilchrist, Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia, Harvard Art Museums, 2016

Darren Jorgensen, ‘Book Review: UnAustralian Art’, Thesis Eleven (https://thesiseleven.com/2024/04/17/book-review-unaustralian-art/)

Elwyn Lynn, ‘Letters’, Artforum 13(4), December 1974

Ian McLean, White Aborigines: Identity Politics in Australian Art, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Ian McLean, ‘Postcolonial Traffic: William Kentridge and Aboriginal Desert Painters’, Third Text 17(3), 2003

Ian McLean, ‘The Necessity of (Un)Australian Art History for the New World’, Artlink 26(1), March 2006

Ian McLean, Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art, Reaktion Books, 2016

Ian McLean, Double Nation: A History of Australian Art, Reaktion Books, 2023

Ian McLean and Terry Smith, ‘Doubled Histories: The Future of Australian Art’, Dispatch Review, 21 December 2023 (https://dispatchreview.info/Double-Histories-Special-Issue)

Howard Morphy, Aboriginal Art, Phaidon, 1998

Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art, Verso, 2013

Ann Stephen, ‘On Rattling Spears’, Art Monthly Australasia 298, May 2017