by Darren Jorgensen (University of Western Australia)

For five decades, Terry Smith has been a crucial part of conversations on both Australian and contemporary art. Since his 1974 essay, ‘The Provincialism Problem,’ through to a series of publications on global contemporary art, Smith has been both prolific and influential in the discipline of art history. This essay traces two influences upon Smith’s oeuvre, these being conceptual art and Aboriginal Australian art, while arguing that his subsequent conceptualisation of ‘contemporaneity’ is both useful and undertheorised. The idea of contemporaniety emerges from Smith’s studies of a worldwide exhibitionary practice (Smith, 2012; Smith, 2015; Smith, 2019). The primacy of exhibitions is also related to conceptual art, that works with dematerialisation and installation rather than objects, and to the trouble that classifying Aboriginal art brought to institutions, as it transitioned from being in museum collections to art gallery displays over the course of the 1970s and 1980s (McLean, 2011: 17-75). The study of exhibitions rather than works of art also marks a change in art history’s disciplinary focus, as a more conventional and older mode of art history focuses instead upon individual works of art. In this sense, Smith’s writing breaks with the discipline’s focus upon questions of nationhood, style, and historical periods, turning instead to the relationship between the situations for the production of works of art, particularly contemporary art, and their exhibition. Focusing upon curators as agents of this exhibition making, Smith maps the differences between artworlds, those discourses that bring art into being (McLean, 2011: 162; Smith, 2012; Smith, 2015). The rise of contemporary art since the 1990s enables us to think about a state of contemporaneity that implies a coevality of difference across geographies and states of duration. These durations correspond to the vast inequalities and irreconcilabilities of global life, the ontological and material strata by which capital implicates human beings across nations, times and spaces. While modernity and postmodernity were periodising concepts that emerged from combinations of economics, literary studies, sociology and geography, contemporaneity arises from art history. The phenomenal methods of art history, its attention to the sensual and visual experience of art, make it ideal for thinking about the highly mediated, screen-based historical experience of the twenty-first century.

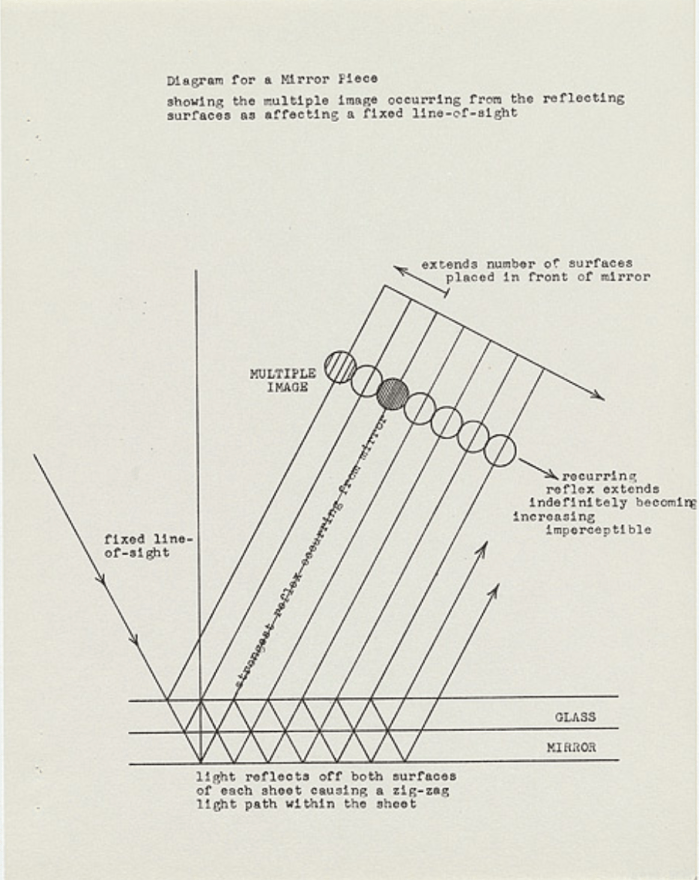

The foundations of Smith’s theory of contemporaneity lie in the impact of two historical moments upon his scholarship. Conceptual art, as Smith experienced it in the early 1970s, overturned the ways of doing things that previous generations of scholars had become accustomed to. Scholarship of the 1960s was motivated by medium and the hierarchies of both artists and genres of art, while conceptual art transcended these with a philosophical reflexivity that shapes the work of art into ideas. Smith describes missing the significance of conceptualism when he first encountered it, walking past Ian Burn’s Two Glass/Mirror Piece (1967-68) and thinking it was ‘one of those anti-painting stunts from the magazines’ (Smith, 2002: 123). Two Glass/Mirror Piece consisted of a mirror framed behind two sheets of glass, and hung amidst hard-edge and colour field paintings as part of The Field, an Australian exhibition in 1968 that introduced geometric abstraction to Australian audiences. Glass/Mirror Piece instead anticipated the impact of conceptualism, which would change the avant-garde game that painters had been playing, as artists emphasised cognitive rather than visual apperception. Smith’s ‘Doing Art History’ is one of the first essays to track the impact of conceptual art upon art history, tracking not only the shift away from painterly language that art history had become accustomed to using, but in troubling normalising ideas that the discipline had become reliant upon, including chronology, the oeuvre, and the separation of artist from scholar (Smith, 1975). After publishing ‘Doing Art History’, Smith went on to join Burn and Mel Ramsden in the conceptual art collective Art & Language in New York, becoming part of the global conceptual art movement, and would later publish as part of a project to think about conceptual art globally, rather than as a movement limited to New York (Smith, 1999).

The second art movement that Smith takes as revolutionary for art history is Australian Aboriginal art. Smith was not alone in being late to recognise the significance of Aboriginal art, but he was the first art historian to write substantially on it. His chapter ‘From the Desert: Aboriginal Painting’ in Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting, 1877-1990 began to rectify the lacuna of art historical writing on Aboriginal art, supplementing publications by anthropologists with a survey of the movement’s geographies, its artists’ intentions, and materiality (Smith, 1991: 495-517). Australian Painting has been a foundational text on Australia’s art history since it was first published in 1962, and Smith’s 1991 chapter was an innovation in placing Aboriginal painting alongside canonical works of Australian art. The previous editions of Australian Painting had made no mention of Aboriginal art, that was instead represented in Australian publishing by anthropological writing (Berndt, 1964; Berndt, 1982; Buhler A, Mountford C and Barron T, 1962; Elkin, Berndt and Berndt, 1950; Mountford, 1953; Mountford, 1958). This apartheid of Australian and Aboriginal art persists to this day, in what the art historian Ian McLean has called a ‘Double Nation’ constituted by two artworlds, the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal (McLean, 2023). Smith’s intervention in Australian Painting remains one of a handful of serious attempts to reconcile the two art histories. McLean notes that Smith saw the potential of Aboriginal art to rethink artworld ideas as early as 1983, asking, ‘What would a history of Aborigines’ representations of whites be like? How has Aboriginal imagery in all its regional forms changed since 1770—or 1606–or earlier?’ (McLean, 2011: 37). Smith’s 1983 essay addresses the dominance of European art history in Australian education, writing of university courses that there were ‘very few looking at Asian art and none on Aboriginal art’ (Smith, 1983: 11). Anticipating the impact of Aboriginal art on his own scholarship, Smith suggests that Aboriginal art offers ways of rethinking art history more broadly.

Smith’s chapter in Australian Painting appeared two years after ‘Aboriginal Art: Its Genius Explained’ (Smith, 1989). The essay anticipates ‘From the Desert’ in surveying what was then the little-documented diversity and geography of Aboriginal art, while also historicising its increasing international profile. ‘Aboriginal Art: Its Genius Explained’ is something of a corrective to the dominance of anthropological accounts of the rise of Aboriginal art as Smith points to exhibitions that brought it into public view during the 1980s. These exhibitions include the survey From Another Continent: Australia, The Dream and The Real at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville in 1983, that preceded Aboriginal Australia’s representation in Paris in the seminal Magicians of the Earth show of 1989. Magicians of the Earth is typically historicised as the beginnings of the globalisation of Western art institutions, its inclusion of artists from around the world alongside famous Western artists marking a beginning for the biennale style of world exhibitions that would become prominent during the 1990s and 2000s (Steeds L, Lafuente P, Poinsot, J, 2013).

Smith also writes of the first survey of paintings from the Central Australian communities of Utopia, Utopia Women’s Paintings: A Summer Project 1988-1989 in Sydney, that exhibited Emily Kame Kngwarreye for the first time (Brody, 1989). Painting in the Central Australian desert, Kngwarreye would go on to become Australia’s most important artist of the 1990s, radically transforming the definition of Aboriginal painting as she changed her mark-making from one type of picture to another, untying desert painting from the conventional iconography of dots and roundels (Smith, 1998). In ‘Aboriginal Art: Its Genius Explained,’ Smith is conscious of the way that this new exhibitionary complex is tied to a nascent, unregulated market, one that Kngwarreye has come to symbolize as her paintings were commissioned and sold by a range of dealers. ‘Aboriginal Art: Its Genius Explained,’ also insists upon an argument about Aboriginal art’s traditionalism that Smith will repeat in different contexts over the next three decades. He writes that:

Reproduced everywhere, the desert paintings are striking witness to the central value at the heart of the case for Aboriginal land rights: an inherited, felt, physical and imaginary identification with a particular place, expressed in a visual language that is both distinctly different but also evidently beautiful. Here we glimpse the full dimension of what would be lost if the modernist art machine does succeed in absorbing Aboriginal art. Not only would the paintings become just a phase in the history of Western art appreciation and marketing, they would lose their edge as social and political statements (Smith, 1992: 185-186).

With this sense of Aboriginal art’s distinct role in Aboriginal societies, Smith took two trips to the Central Desert in 1989 and 1993. In 1993 he visited the sacred ochre mine of Karrku, located in a mesa in the depths of Warlpiri country. Smith helped dig purple coloured ochre out of the mine, and heard the artist Paddy Japaljarri Sims tell the story of the Country around there:

He put a few dabs of the ochre on his face and immediately started speaking to me, pointing out across the landscape. It was mainly scrub desert with a few other mesas, a vista stretching as far as one could see. Glen did some translating. Paddy was telling me the story of the place, about the ancestor who carried the ochre, misbehaved with two sisters, and much else besides. I started to see shapes and forces moving across the desert in front of us as he named all the features as part of an elaborate story, of which I was only getting glimpses. On the way back in the truck he insisted on sitting next to me and kept talking, a hour or so to Nyirripi and then most of the way back to Yuendumu. Glen gave up translating but let me know that Paddy was welcoming me into his family, as a Jungarrayi his eldest son, befitting my rank as a professor from Sydney. Although I could not understand the details of what I was being told, I understood the intent. I visited him at his place each day for a few more days before I left (email to the author, 9 October 2025).

This intimate contact with a senior lawman of the Central Desert reinforced Smith’s argument for the specificity of Aboriginal art, for a traditionalism that he will come to argue is also an anti-modernism. The visit also gave Smith a sense of the collectivist society from which Australian Aboriginal art emerges, as when Smith visited him, Sims was involved in a collective project to paint Karrku alongside other traditional owners of the site (Morphy, 1998: 300-303). Commissions to document the Dreamings of sites like Karrku were part of museum practice during the 1990s, as institutions and local interlocutors commissioned large, collaborative works for their collections. Being close to one of these projects, and to the traditional authority of Sims who bore traditional responsibility for Karrku, undoubtedly influenced Smith’s persistence in returning to Aboriginal art’s geographical and spiritual grounding in remote Australia.

The continuity of Smith’s position here is remarkable, as his insistence upon the land-based politics of Aboriginal art resists the discourses and ideologies of modernism insofar as they persisted within art history. The argument ran counter to art history’s interest in mapping art movements from around the world in the twentieth century, as art historians influenced by both contemporary art and postcolonialism began to formulate an expanded, global account of multiple, geographically and culturally diverse modernisms. Crucial to the scholarship on multiple modernisms is an interest in Indigenous artists whose historical experience of colonialism enabled them to create new, hybrid genres of art practice (Harney, Phillips, Thomas, 2018; Phillips and Vorano, 2025). Amidst this interest in renewing definitions of modernism, Smith continued to insist upon the traditionalism of Aboriginal art as remote communities struggled with the ongoing impacts of colonialist modernity. To make his anti-modernist argument, Smith draws upon both anthropological writing on Aboriginal art and the words of the artists themselves as they insist upon the ancestral continuity of their artworks that express the deep time of their relationship to Country, a capitalised term used in Australia to recognise this relationship (Smith, 2013; Smith, 2019). Smith wants to emphasise ‘the sufficiency of local values, not least in their direct expression of ‘universal’ values,’ the way that this ancestral domain is one that can be communicated and partly comprehended through visual arts (Smith, unpublished essay). In David Joselit’s terms, Smith wants to emphasise the heritage of Indigenous artists rather than their debt to Western art’s influences. Joselit’s Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization describes the way that heritage is used to enact the reparative justice amidst the flows of global capital and after the injustice of colonialisation (Joselit, 2020: 102-111). Aboriginal artists emphasise their heritage in order to refuse a debt that is both cultural and literal as Third and Fourth world artists are implied in a relationship of financial dependence upon First World wealth. The argument replays something of Smith’s ‘The Provincialism Problem,’ as Joselit uses the hierarchies of twentieth century economics to describe the place of artists within the hierarchies of global culture industries (Smith 1974). Smith’s emphasis upon the traditionalism of Aboriginal artists proposes instead that this heritage represents an ontological difference within the circulation, exhibition and representation of cultural forms. Indigenous traditions present a differend among differences, that demand to be thought both in absolute and relative terms, in order to take seriously the way in which these traditions reproduce inalienable claims to ancestral knowledge and land (Lyotard, 1988).

Smith’s caution over the use of the term modernism can be traced back to his generation’s resistance to its influence over the formalist art discourses of the 1960s. Art critic Clement Greenberg’s visit to Australia, and his dismissal of painting practices in Sydney and Melbourne, played a role in Smith’s disillusionment with the impossible hierarchies at work within modernism, and his enthusiastic embrace of conceptualism (Smith, 1969). Smith’s position plays itself out within debates in Australia too, where McLean argues that colonialism brought about the transcultural transformation of Aboriginal artists (McLean, 2016). For McLean, the anti-colonialism of Aboriginal art is symptomatic of the modernity of its artists, contrary to Smith, who draws instead upon accounts of the continuity of Indigenous identity under colonialism, and for whom their anti-colonialism is an anti-modernism. Smith’s attention to the margins of global art production is also in evidence in ‘The Provincialism Problem’ (Smith 1972). Here, Smith uses the idea of Australian art to argue that art produced in the 1970s, whether in Sydney or New York, carries with it a sense of being always outside the leading edge, as its ‘provincialism’ reproduces the sense that there is an elusive centre of contemporary art production. In ‘The Provincialism Problem: Then and Now’ (2017), Smith returns to ‘The Provincialism Problem’ to re-emphasise its critique of what he describes in the opening line of his 1974 essay as the ‘massively unequal—indeed, iniquitous world art system’ (Smith, 1974, 54). Smith recalls the hope that his generation had an ‘avant-garde possibility’ that might overturn this system (Smith, 2017: 14).

Charles Green and Heather Barker have recently argued that a precedent for this argument about avant-gardism lies in one of Smith’s earlier essays on a movement of colour field painters in Sydney in the late 1960s (Green and Barker, 2024: chapter 3). They describe a shift in Smith’s thinking in his 1970 essay ‘Color-Form Painting’ (Smith 1970). After initially proposing that artists even in remote centres could produce an avant-garde situation for themselves by doing something innovative and new, he goes on to consider the Sydney painters he is writing about as less innovative than they first appeared. While these ‘Color-Form Painters’ offered something genuinely new to the history of international painting, they also failed as an avant-garde, as their art lacked the content that would otherwise afford them a truly compelling place within art’s history. It is as if, as Green and Barker point out, ‘Smith talked himself out of an idea–and out of the model of stylistic differentiation determining innovation–in the process of writing his argument and developing a self-consciously art-historical treatment of Australian contemporary art’ (Green and Barker, 2024: chapter 3). In ‘The Provincialism Problem’, the failure of the avant-garde is embedded within all provincial practices, and more crucially, within the ways that art criticism and history were being written at this time (Smith, 1974). It was impossible for Smith to account for the originality of the Sydney ‘Color-Form Painters’ on their own terms, as the dominant and modernist logic of the avant-garde demanded that he describe them in relation to the international originality of their practice. ‘Color-Form Painting’ plays out an unravelling of modernist modes of doing art history, as Smith shifts position in this essay from arguing for the avant-gardism of their practices to the inevitable failure of this avant-gardism.

The break with modernism was a defining feature of Smith’s generation of art historians, who faced the challenge of defining the historical situation for artists without recourse to avant-garde ideals. The defining moment in Smith’s consolidation of contemporaneity as an answer to this theoretical problem was a meeting he co-convened with Okwui Enwezor and Nancy Condee in 2004, the proceedings of which were published in 2008 as Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity (Condee, Enwezor and Smith, 2008). Here contemporaneity was proposed alongside theories of modernity and postmodernity, that along with globalisation, dominated periodising descriptions of the world situation during the 1990s and early 2000s. Notably absent from Antinomies is a paper from Fredric Jameson, who presented at the meeting but did not publish alongside the others. Smith describes Jameson’s resistance to the idea of contemporaneity, reporting that he ‘expressed doubt as to whether the concept of contemporaneity was adequate’ to thinking the historical present (Smith, 2008: 19).

As a description of the cultural effects of globalisation, contemporaneity rivals Jameson’s theorisation of postmodernism, with their crucial difference being in their accounts of the Third and Fourth Worlds. The origins of theories of postmodernism, including Jameson’s, date to the late 1970s and 1980s, before the end of the Cold War and as First World countries experienced ‘a new depthlessness’ of cultural production (Jameson, 1984: 58). In his 1991 book Jameson develops the insights of his original 1984 essay into concepts of ‘pastiche’ and a ‘waning of affect’ that best describe the effects of consumer capitalism (Jameson, 1991: 10-25). This early account of global capitalism was critiqued for brushing over the differentiated experiences of third and fourth world peoples (Colas, 1992; Spivak, 1992: 14-15). Smith’s model of contemporaneity has the advantage of incorporating a consciousness of postcolonial experience, as well as post-communism that existed alongside First World art and cultural production during the 1990s and 2000s. In publications including What is Contemporary Art? and Art To Come: Histories of Contemporary Art he uses the experiences of Aboriginal Australian and Chinese artists becoming part of the global market to emphasise their contemporaneity, the differences upon which their practices rest (Smith, 2009; Smith, 2019). The successes of Aboriginal artists such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye are in dramatic contrast to their lived experience, for example, Kngwarreye’s childhood growing up in poverty on the cattle stations of Central Australia, supplementing rations with hunting and gathering. Similarly, the generation of China’s contemporary artists who rose to prominence during the 1990s and 2000s were born into unimaginably different circumstances. These artists were children during the mass displacement and violence of the Cultural Revolution, coming of age amidst the Opening and Reform policies of the 1980s, only to experience increasingly draconian state policies as China boomed economically (Li, 2024). These artists are not the product of the consumer society that postmodernity defined, but came to contemporary art from lives that are incommensurable with the economic and cultural backgrounds of most Western critics, curators, and scholars attempting to account for their presence within the artworld’s economic and exhibitionary systems.

It is worth pausing upon this particular difficulty, and Smith’s place amidst competing theories of contemporary art and contemporaneity as well as within debates in Australian art history. Smith’s mediation of the margins of contemporary art with its centres has been a central concern of his writing, and one that also makes him vulnerable to misinterpretation. Most recently, Joselit’s Heritage and Debt represents the most ambitious attempt to come to terms with the globalisation of contemporary art since Smith’s duology What is Contemporary Art? and Contemporary Art: World Currents (Smith 2009; Smith 2011). Joselit takes a quote from the first of these books as an argument for ‘market-driven contemporaneity,’ but as Smith points out in a review of Heritage and Debt, What is Contemporary Art? sets out to make the opposite point (Joselit 2020: 33). Smith’s first chapters in What is Contemporary Art? take aim at the making spectacular of contemporary art in a critique of the most influential institutions of the world, including the Museum of Modern Art and Dia: Beacon in New York, the Tate Modern in London and the Bilbao in Basque Country, Spain (Smith 2009). The point was to critique these centres before the later chapters of the book address postcolonial and postsocialist movements including Aboriginal Australian and Chinese contemporary art.

This interest in tackling the power hierarchies of contemporary art, part of the continuity of Smith’s practice since ‘The Provincialism Problem,’ has been more substantially critiqued by Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson in their radicalization of Australian art history as an UnAustralian art history (Butler and Donaldson, 2007). Butler and Donaldson create a transnational model for contemporary art history by documenting the many Australian artists who lived and worked overseas, or who came from overseas, bringing their (largely) European influences to Australia. The model is one that avoids the canonisation of Australian artists represented most influentially by Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting, 1877-1990, that celebrated landscape painters such as Arthur Streeton and figurative innovators including Sidney Nolan(Smith, 1991). Butler and Donaldson instead turn to relatively minor figures within Australian art, creating a diffuse geography of artists and their movements that no longer casts Australians as provincial within an international picture of modern art (Butler and Donaldson 2012). Smith is in turn critical of their ‘UnAustralian art’ project to de-canonize Australian art history by arguing that they ‘miss the fact that provincialism was enacted through the pattern of expatriation described above, and seem to think that mere connection refutes the operations of cultural power’ (Smith, 2017: 28-29). This focus upon the artworld’s structures of power keeps Smith’s conceptualisation of the contemporary focused upon its most prominent Euro-American sites of display, all the while through a postcolonial lens. In this sense, Smith’s twenty-first century writings on contemporary art, including What is Contemporary Art? reproduce the mediation represented by ‘The Provincialism Problem’ between the local and global, peripheral and powerful, in a lifelong attempt to grapple with the implications of art’s circulation and exhibition across nations, cultures and peoples (Smith 1974; Smith 2009). For Smith, those who are marginal are those underrepresented by global exhibitions and museums, as his work is haunted by contemporary art’s exhibitionary complex, its tendency to aggregate in major centers of the world such as London, Paris and New York (Smith, 2012: chapter 2). This aggregation is both evidence of the inequality of the artworld’s distribution of power and a problem for theorists of contemporaneity, as critiquing this power is necessarily doubled by an attention to the margins that it expropriates.

Crucially, Smith’s proposition to use contemporary art to think more broadly about global history has been overlooked in a rush to understand the theoretical problem of contemporary art itself. What is Contemporary Art? is widely used as an undergraduate textbook in art history, while anecdotally and since its appearance in 2019, I have used Art To Come: Histories of Contemporary Art as a primary reader for a second year university course in contemporary art (Smith 2009; Smith 2019). Smith’s readership is more general than this, as curators and arts workers also draw upon it to inform their labour. Testament to this lies in an interview with one of the world’s leading curators, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, in which she turns the tables on Smith and asks about his own publications and work, revealing the influence he has had on her (Smith, 2015: 37-59). Anecdotally, once again, a local arts worker I know working in a university gallery keeps a copy of Art To Come in his desk in a collection store for inspiration. Smith’s focus upon exhibitions as well as artists or artworks has led him to pay tribute to curators in publications including Talking Contemporary Curating and Thinking Contemporary Curating, that work through the question of precisely how and when contemporary art became of historical significance (Smith 2012; Smith 2015). In these books, Smith sets out to understand how contemporary art assumed a relevance not only to the artworld but to a sense of its own worldliness, as artists and curators became conscious of the way in which their practices engaged with the circulation of ideas in an increasingly connected, post-national atmosphere for making exhibitions.

Proposing that the concept of contemporaneity is pertinent not only to this artworld context but to the broader historical situation marks a major shift for art historical study. Since the 1960s art history has been largely parasitic upon methods developed in literary studies, a practice that was most visible in the 1980s in journals such as October and Art & Text, that published during postmodernism’s discursive peak. The definition of modernism and postmodernism in this body of art history and theory was principally textual, as its authors borrowed lavishly from semiotic and poststructuralist texts. This is not to say that the visual arts were not part of the overall conceptualization of modernism and postmodernism, but that the method by which the visual arts were interpreted was principally textual (Jameson 1991: 67-95). The publication of Antinomies represents a turning of this traffic of ideas as it proposes contemporaneity as a periodising concept through an immersion in the discursive, exhibition and studio practices of the visual arts. Contemporaneity is not defined phenomenally and visually, corresponding with the increasingly screen-based experience of the world that is both textual and pictorial. Contemporaneity addresses the problems of historical totality and periodisation that both modernity and postmodernity defined, taking contemporary art rather than books and films as its principal site to exemplify the experience of the twenty-first century.

The origins of the concept of contemporaneity within Smith’s work lie in conceptual art and Australian Aboriginal art. These influences are both distinct and related as they give rise to arguments around provincialism and traditionalism respectively. Through these two influences it is possible to think contemporaneity historiographically, as the idea emerges from a turn away from modernism and toward a diffuse and diverse, postcolonial artworld. In this sense, this essay is an author study of Smith, but wants to push beyond the author himself as the subject of the essay, as it aims to elaborate the beginnings of a concept of contemporaneity for thinking the historical present. There are other areas of Smith’s thinking that situate his scholarship within art history, but that may be less useful in creating a context for the development of contemporaneity. An essay on Gustave Courbet’s The Stonebreakers (1996) confronts the Marxist or social history of art within the changes wrought by the discourse on postmodern, consumer society (Smith, 1996). A book on architecture after September 11, 2001 allows us to glimpse a whole other area of Smith’s writing on what he calls iconomy, that has included books on architecture and visual culture (Smith, 2006; Smith, 2022). There has also been an influential book on art and design in America, and edited books on photography and Jacques Derrida (Smith, 1993; Smith and Patton, 2001; Smith, 2001). This range of interests, this grasp of and responsiveness to both historical and intellectual currents, has consistently attended to what is most pressing in the historical situation Smith is living through, while speculating upon the significance of the complex multivalence of images and works of art. Thinking this world totality alongside the specificity of contemporary art, along with the breadth of his concerns and sustained critical practice, mark Smith out as one of the most compelling art historians of his era. Smith’s legacy, however, is limited by this breadth of work, within which several concepts lie undeveloped and undertheorised. Contemporaneity is one of these concepts.

References

Berndt RM (1964) Australian Aboriginal Art. Sydney: Ure Smith.

Berndt RM (1982) Aboriginal Australian Art: A Visual Perspective. Sydney: Methuen.

Brody A (1989) Utopia Women’s Paintings: The First Works on Canvas: A Summer Project 1988–89: The Robert Holmes à Court Collection. Sydney: Heytesbury Holdings.

Bühler A, Mountford C and Barron T (1962) Oceania and Australia: The Art of the South Seas. London: Methuen.

Butler R and Donaldson ADS (2007) Was Australian art ever provincial? A response to Terry Smith’s ‘The provincialism problem: Then and now’. ARTMargins 6(1): 6–32.

Butler R and Donaldson ADS (2012) UnAustralian Art: Ten Essays on Transnational Art History. Sydney: Power Publications.

Colás S (1992) The third world in Jameson’s Postmodernism, or, The cultural logic of late capitalism. Social Text 10: 258–270.

Condee N, Smith T and Enwezor O (eds) (2008) Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Elkin AP, Berndt RM and Berndt CH (1950) Art in Arnhem Land. Melbourne: Cheshire.

Green C and Barker H (2024) When Modern Became Contemporary Art: The Idea of Australian Art, 1962–1988. London: Taylor & Francis.

Harney E, Phillips R and Thomas N (eds) (2018) Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jameson F (1984) Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism. New Left Review 146: 53–92.

Jameson F (1991) Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Joselit D (2020) Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Li X, Jorgensen D and Fleming K (2024) Li Xianting: In conversation with the hooligan. Guan Kan: Thinking with Contemporary Chinese Art, 16 October, 2025. Available at: https://www.guankanjournal.art/journalessays/sv0s269g4mun57egyikj688go23fkt

Lyotard J-F (1988) The Differend: Phrases in Dispute. Trans. Van Den Abbeele G. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McLean I (2011a) How Aborigines invented the idea of contemporary art. World Art 1(2): 161–169.

McLean I (2011b) How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art. Brisbane and Sydney: Institute of Modern Art and Power Publications.

McLean I (2016) Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art. London: Reaktion.

McLean I (2023) Double Nation: A History of Australian Art. London: Reaktion.

Morphy H (1998) Aboriginal Art. London: Phaidon.

Mountford C (1953) The Art of Albert Namatjira. Melbourne: Bread and Cheese Club.

Mountford C (1958) The Tiwi: Their Art, Myth and Ceremony. London: Phoenix House.

Patton P and Smith T (eds) (2001) Jacques Derrida, Deconstruction Engaged: The Sydney Seminars. Sydney: Power Publications.

Phillips R and Vorano N (eds) (2025) Mediating Modernisms: Indigenous Artists, Modernist Mediators, Global Networks. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Smith T (1969) The style of the sixties. Quadrant 14(2): 49–53.

Smith T (1970) Color-form painting: Sydney 1967–70. Other Voices 1(1): 6–17.

Smith T (1974) The provincialism problem. Artforum 13(1): 54–59.

Smith T (1975) Doing art history. The Fox 2: 97–104.

Smith T (1983) Writing the history of Australian art: Its past, present and possible future. Australian Journal of Art 3: 10–29.

Smith T (1989) Aboriginal art: Its genius explained. The Independent Monthly, September: 18–19.

Smith T (1991) From the desert: Aboriginal painting. In: Smith B with Smith T Australian Painting: 1788–1990. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 495–517.

Smith T (1992) The genius of Black art. In: Devine F (ed.) Best of the Independent Monthly. Geelong: Deakin University Press, 183–189.

Smith T (1993) Making the Modern: Industry, Art and Design in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith T (1996) Production: The specter and The Stonebreakers. In: Nelson R and Shiff R (eds) Critical Terms for Art History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 361–381.

Smith T (1998) Kngwarreye: Woman abstract painter. In: Isaacs J (ed.) Emily Kngwarreye Paintings. Sydney: Craftsman House, 24–42.

Smith T (1999) Peripheries in motion: Conceptualism and conceptual art in Australia and New Zealand. In: Camnitzer L, Farver J and Weiss R (eds) Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950s–1980s. New York: Queens Museum of Art, 86–98.

Smith T (2002) Transformations in Australian Art: The Twentieth Century—Modernism and Aboriginality. Sydney: Craftsman House.

Smith T (2006) The Architecture of Aftermath. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith T (2008) Introduction: The contemporaneity question. In: Smith T, Enwezor O and Condee N (eds) Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1–19.

Smith T (2009) What Is Contemporary Art? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith T (2011) Contemporary Art: World Currents. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith T (2012) Thinking Contemporary Curating. New York: Independent Curators International.

Smith T (2013) Thinking contemporary art, world-historically. Keynote lecture, Reimagining Modernism; Mapping the Contemporary: Critical Perspectives on Transnationality in Art. CRASSH, Churchill College, University of Cambridge.

Smith T (2015) Talking Contemporary Curating. New York: Independent Curators International.

Smith T (2017) The provincialism problem: Then and now. ARTMargins 6(1): 6–32.

Smith T (2019) Art to Come: Histories of Contemporary Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Smith T (2022) Iconomy: Towards a Political Economy of Images. London: Anthem Press.

Smith T (ed.) (2001) Impossible Presence: Surface and Screen in the Photogenic Era. Sydney and Chicago: Power Publications and University of Chicago Press.

Spivak GC (1999) A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Steeds L, Lafuente P and Poinsot J (2013) Making Art Global (Part 2): Magiciens de la Terre, 1989. London: Afterall.