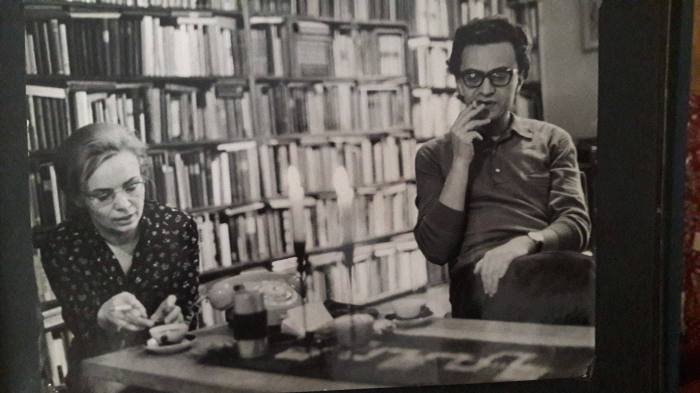

Maria Markus. In Memoriam

Issue 151, April 2019

Editorial:

Editors’ Intro

John Grumley, Pauline Johnson

It is now eight years since Thesis Eleven published a Festschrift for Maria Márkus. Since then things have changed. Maria died over a year ago in September 2017. The world has been over-turned too. Rightist politics have gripped Eastern Europe, Donald Trump is in the White House, xenophobic populist movements have been energised across the globe and the future of the European Union is up for grabs. It’s time for reflection, for the weighing of losses and for a renewed ‘saving’ interest in Maria’s key themes and preoccupations about building civility in our institutions and decency in our relationships. It’s time also for contemplation about the loss of Maria from our lives. We have invited some explicit reflections on the unique, the unforgettable, Maria and encouraged contributors who also knew her to talk about her significance for them. Personally, we still find it hard to take in the fact that she is gone from our lives. Perhaps more than anyone else that we have known, Maria embodied life itself. She was a living presence that is but poorly captured in the apt descriptions of: vitality, intelligence, devotion, courage, integrity, love of fun, truthfulness, ethical self-restraint and more. We are very grateful that Maria’s youngest son Andras Márkus has allowed us to publish his moving and thoughtful Eulogy.

Obituary:

‘Anyu’

Andras Markus

In memoriam of Maria Márkus

Iván Szelényi

Thinking about Marysia

Ágnes Heller

Remembering Maria, 1978–2017

Mira Crouch

Articles:

The discreet charm of civility

Martin Krygier

Maria Márkus took special interest in the concept of civil society that was revived by East European dissidents and incorporated it into her account of the fundamental ideals of modernity. Modern societies were civil to the extent that they possessed a ‘public sphere’ that incorporated structures and mechanisms of action and communication able to form, articulate and press the interests and needs of the society on public agencies; and to defend them, if the state ignores or seeks to override them. This article discusses the relationships in her thought between civility, civil society and decency. She sees the first as a condition for the second, but not a part of it, while decency is both an accomplishment and attribute of a civil society in good shape. For her, a decent society is the ideal to strive for, a civil society the way to get there, civility a necessary step toward civil society, and therefore too for a decent one, but not a huge step. This article suggests that civility deserves more than the lukewarm approval Maria bestowed upon it. In particular, the piece tries in some measure to bridge the gap she saw between civility, on the one hand, which she appreciated in a kind of ‘two cheers’ way, and civil and decent societies, on the other, which received her full (and fully warranted) three-cheers.

Success, Needs and Decency: For Marysia Márkus

John Grumley

In the following paper I will analyse three key themes characteristic of the life and work of Marisha Márkus. This paper was originally read for a conference on her work at the time of her farewell from the University of New South Wales in 2002. Success, Needs and Decency are signature themes that percolate through her work. Under the theme of success I turn to central ideas in her early sociology of women and to the meaning of success in the world of the life of women. This theme has a particular existential theme for Marisha, who nursed her eldest son Gyuri for the last 30 years of her life. The concept of radical needs was a central concept of the work of the Budapest School. Marisha’s relatively less well-known interpretation of needs is arguably the most fully democratic reading of this theme that came to be better known in the work of Agnes Heller. I finally turn to the concept of decency, which for Márkus adds value to the key ideal of civil society that became so important in the transition of so-called socialist societies during the collapse of the communist regimes in the Eastern bloc.

Do political theorists have friends? Towards a redefinition of political friendship

Harry Blatterer

This article suggests a sensitising definition of political friendship with the view of using the concept in empirical research. I begin by identifying three tendencies in the recent literature on political friendship: (1) the tendency to ignore historical developments that rendered modern friendship an intimate relationship; (2) the construction of modern friendship as hermetically sealed in the private sphere; and (3) the conceptual conflation of relationship types. Consequently, friendship is emptied of substantive relational content, while political ‘friendship’ is promoted from metaphor to denotative concept. I critique that approach by drawing on Maria Márkus’s account of friendship, which emphasises its historically contingent, ambiguous position between the private and the public spheres whence friendship offers vital utopian potentials in respect of public life: friendship instantiates mutual self-determination and gives experiential substance to ‘decency’. Combining Márkus’s with a differentiating approach to friendship that takes its lead from Siegfried Kracauer, I go on to propose a preliminary redefinition of political friendship as a personal relationship, as well as the substitution of political friendship by democratic solidarity with ‘decency’ its guiding orientation.

Learning from the Budapest School women

Pauline Johnson

What can Western feminism hope to learn from women whose feminisms were originally shaped by experiences behind the ‘Iron Curtain’? In the first instance, an acute sensitivity to the importance of a politics that is responsive to needs. In its social democratic heyday, Western feminism had embraced a politics of contested need interpretation. Now, though, a neoliberal version has converted feminism into an attitudinal resource for the individual woman who is bent upon success. The takeover was made easy by the poor self-understanding of social democratic feminism. My paper will compare Agnes Heller’s theory of ‘radical needs’ and Maria Márkus’s account of the ‘politicization of needs’ and apply both to the normative clarification of endangered feminist agendas. We look to the Budapest School women for more than just a way of conceptualizing the political radicalism of modern feminism as a social movement. Women need heroes too and a reflection upon the dignified and admirable lives of Agnes Heller and Maria Márkus has much to contribute to an ongoing search for a feminist ethic of the self.

Mess is more: Radical democracy and self-realisation in late-modern societies

Norbert Ebert

The following discussion highlights the sociological relevance of Maria Márkus’s work for the Budapest School’s concept of ‘radical democracy’. A brief historical sketch exhibits how the concept has emerged. It is in particular the ‘messy’ social conditions for equal and free forms of self-realisation in civil society that underpin radical democracy which are central in Maria Márkus’s critique of the neoliberal state, identity formation and a gendered achievement principle. Her approach, I argue, can be advanced as a prism for the critical analysis of contemporary issues. To do so, I contend that late-modern societies are increasingly defined by a paradox with a pluralisation of identity claims in civil society on the one hand, and tendencies to homogenise identities on the other by concurring economic and political forces. A democratisation of everyday life, and with it diverse and plural forms of self-realisation, appears to be under homogenising pressures from governments and markets alike. This will be briefly demonstrated using Maria Márkus’s work, which also points toward possible departure points to advance a critical sociology of radical democracy.

Beyond a socio-centric concept of culture: Johann Arnason’s macro-phenomenology and critique of sociological solipsism

Suzi Adams

This essay unpacks Johann Arnason’s theory of culture. It argues that the culture problematic remains the needle’s eye through which Arnason’s intellectual project must be understood, his recent shift to foreground the interplay of culture and power (as the religio-political nexus) notwithstanding. Arnason’s approach to culture is foundational to his articulation of the human condition, which is articulated here as the interaction of a historical cultural hermeneutics and a macro-phenomenology of the world as a shared horizon. The essay discusses Arnason’s elucidation of his theory of culture as a contribution to debates on the ‘meaning of meaning’. It traces its beginnings from his critique of Habermas’s theory of modernity to its development via a trialogue with Max Weber, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Cornelius Castoriadis. It argues that Arnason’s theory of culture moves beyond socio-centric perspectives, and, in so doing, offers a critique of what we might call sociological solipsism. In decentring society/anthropos, a more nuanced understanding of the human condition as a unity in diversity is achieved. The essay concludes with a discussion of some tensions in Arnason’s understanding of culture, and argues for the importance for incorporating a qualitative notion of ‘movement’ in order to make sense of historical novelty and social change.

Joel S. Kahn (1947–2017) – Perennial anthropologist

John Rundell

Book reviews:

Book review: Another Marx: Early Manuscripts to the International

Peter Beilharz

Book review: The Presentation of Self in Contemporary Social Life

Kieran Flanagan

Pingback: Agnes Heller (1929-2019) | thesis eleven